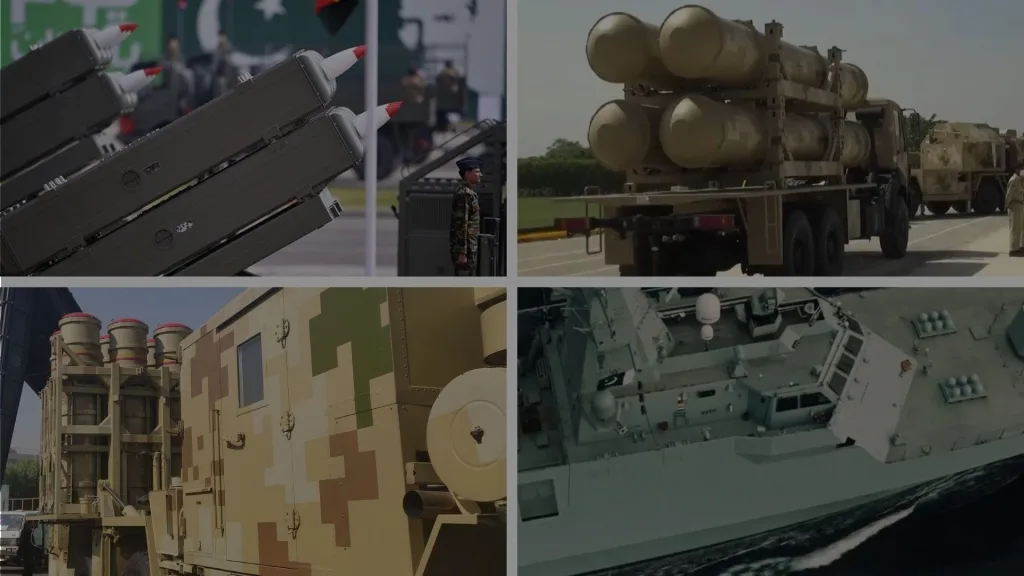

Since the start of the Russia-Ukraine War, ground-based air defence systems (GBADS) have taken on more importance and urgency, with many countries increasing their investment in short-, medium-, and long-range surface-to-air missiles (SAM). Pakistan is no different. Since 2022, the Pakistan Army (PA), Pakistan Air Force (PAF), and Pakistan Navy (PN) have each made acquiring new SAMs and radars a key priority in their respective procurement modernization programs.

Today, each of the Pakistani military’s tri-services is focused on acquiring longer-ranged solutions with more sophisticated features, such as limited anti-ballistic missile (ABM) capabilities.

Imports (mainly from China and, to a lesser extent, Europe) are driving Pakistan’s air defence projects, investment in indigenous solutions is growing, paving the way for domestic industry players to take on long-term requirements.

Traditionally, SAMs were not at the center of the PAF’s operational planning. In fact, until 2019, the PAF’s longest-range SAM system was the Spada 2000-Plus, a short-range system with a reach of 20 km. For the PAF, SAMs were a means of providing low-level protection for facilities, like air bases, and not a strategic factor akin to multirole fighter aircraft.

This changed after 2019. Since then, the PAF has begun leveraging SAMs for territorial defence by acquiring both long-range and medium-to-long-range systems.

From miniature air-launched cruise missiles (ALCM) to kamikaze drones to handheld precision-guided weapons, Pakistan is quietly building a strong loitering munitions portfolio.

Read More

While localized air defence solutions are a goal, the Pakistani military’s near-term acquisitions will primarily be driven by imports. Currently, China has taken up the bulk of Pakistan’s SAM purchases, while Europe and the United States have split Pakistan’s radar needs.

While cost plays a role, it may not be the deciding factor. For example, when it comes to radars, the PAF and the PN have shown a willingness to buy American and Western European systems. These include the Lockheed Martin TPS-77 MRR, a Hensoldt update kit for the MPDRs, and a new batch of Saab Erieye AEW&C platforms, among others. Thus, for the foreseeable future, Western vendors will likely have considerable opportunity in the PAF and PN’s respective radar requirements…

Log in or subscribe to read the rest of the article

Timely Defence News with Verified Insights

Get the latest Pakistani defence news backed by verified sources and insightful analysis.

Click Here

The Pakistan Army’s Air Defence Program

The PA’s air defence efforts are organized under its ‘Comprehensive Layered Integrated Air Defence’ (CLIAD) system. CLIAD is a multi-layered system consisting of short-, medium-, and long-range SAM systems as well as their accompanying surveillance and targeting radars.

Long-Range

For long-range coverage, the PA uses the Chinese HQ-9/P, which it classifies as a ‘High-to-Medium Air Defence System’ (HIMADS). The HQ-9/P utilizes an active radar-homing (ARH) seeker paired with an inertial navigation system (INS). The accompanying HT-233 phased-array fire control radar guides the HQ-9 missile via data-link until a certain point, at which point the ARH activates to independently guide the SAM until it is in proximity to the target. The HQ-9/P has a stated range of 125 km.

Medium-Range

The PA’s medium-range systems are the LY-80 and LY-80EV, which it classifies as ‘Low-to-Medium Air Defence Systems’ (LOMADS). The LY-80 and LY-80EV offer ranges of 40 km and 70 km, respectively, and appear to rely on IBS-150 S-band passive electronically scanned array (PESA) surveillance radar as well as several L-band fire control radars, which can reach 150 km and 85 km, respectively. These SAMs use a semi-active radar-homing (SARH) seeker paired with INS, meaning, they rely on the fire control radar to maintain a lock on the target from launch until the missile reaches the target.

Short-Range

The PA’s short-range layer is split in two segments: ‘Extended Short-Range Air Defence System’ (E-SHORADS) and Short-Range Air Defence System (SHORADS).

The primary E-SHORADS solution is the Chinese FM-90, an export variant of the HQ-7, which itself is a Chinese-built version of the French Crotale. The FM-90 missile uses a command-guidance system.

This is where a fire control computer uses information from a radar to calculate trajectory and other data to determine the best course for intercepting a target. The computer feeds this information to the missile via data-link until the SAM is in proximity to the target.

The FM-90 SAM has a range of up to 15 km and is capable of engaging low-flying aircraft, including drones, helicopters, and, potentially, guided munitions.

In terms of the SHORAD layer, the PA uses a number of MANPADS, including the Saab RBS-70 NG (range: 9,000 m), Chinese FN-6 and FN-16 (range: 6,000 m), and indigenously produced ANZA-Mk2 and ANZA-Mk3 (range: 5,000 m).

Before the formation of CLIADS, the PA’s anti-air coverage was limited to SHORAD ranges. Since the mid-2010s, the PA progressively extended its reach to medium-range and long-range coverages.

The PA likely made this shift to rely less on the PAF for protection against aerial threats, especially for its forward-deployed units. These units, which include precision-guided ballistic missiles (such as the Fatah-series) would need protection from low-flying and high-altitude aerial threats.

By ‘decoupling’ its reliance on the PAF for air cover, the PA could potentially move its strike formations faster. It would not need to worry about a potential bottleneck in PAF fighter availability, for example. It is worth noting that the PA is also building its own long-range strike capabilities via ballistic missiles as well as drones, further indicating its desire to manage offensive operations independently of the PAF.

This is not an indictment on the PAF. Rather, the PA and PAF may have concluded that their respective strike targets are different. For example, the PAF could be focused on using airpower in a concentrated way for strategic outcomes (like Swift Retort), while the PA needs long-range strike capabilities to help operations at a more tactical level (like destroying bridges, eliminating enemy radars, etc).

Pakistan Air Force’s Strategic Air Defence Focus

Traditionally, SAMs were not at the center of the PAF’s operational planning. In fact, until 2019, the PAF’s longest-range SAM system was the Spada 2000-Plus, a short-range system with a reach of 20 km. For the PAF, SAMs were a means of providing low-level protection for facilities, like air bases, and not a strategic factor akin to multirole fighter aircraft.

This changed after 2019. Since then, the PAF has begun leveraging SAMs for territorial defence by acquiring both long-range and medium-to-long-range systems.

Regional Air Defence Umbrella

The PAF recently disclosed that it operates the Chinese HQ-9BE. This long-range SAM has a range of 260 km and a maximum altitude reach of 27 km against combat aircraft. It can also intercept munitions, such as air-to-ground missiles, up to a range of 50 km and altitude of 18 km. The HQ-9BE can engage cruise missiles up to a range of 25 km and an altitude of at least 0.02 km.

The HQ-9BE may be the foundation for a regional air defence umbrella, one that helps neutralize – if not deter – enemy air activity near the border and, potentially, stop ballistic missiles. It is worth noting that the HQ-9BE offers limited ABM capability against tactical ballistic missiles (TBM).

Area-Wide Air Defence Umbrella

The PAF also inducted the HQ-16FE medium-to-long-range SAM. This system has a maximum range of 160 km and altitude reach of 27 km against combat aircraft. The HQ-16FE uses a dual-mode SARH and ARH seeker. In other words, it can operate like either the LY-80/EV or the HQ-9BE/P.

The HQ-16FE uses a 2D active-scanning phased-array radar with a range of 250 km for surveillance as well as target tracking and guidance. This radar has a range of 250 km and can track 12 targets at the same time as well as engage 8 simultaneously.

The PAF likely uses the HQ-16FE to complement the HQ-9BE, creating multiple layers of coverage that cut across multiple ranges and altitudes. This is similar in approach Russia takes with the S-400 where the system actually comprises multiple types of SAMs with varying ranges.

Short-Range Coverages

The PAF is also improving its short-range and point-defence coverages. For example, it is upgrading the Spada 2000-Plus into the Spada Close-in-Weapons System (CIWS). The Spada CIWS will likely pair the existing Spada 2000-Plus system with an Oerlikon GDF 35 mm AAG. In addition, the PAF is looking at replacing the sensors with homegrown solutions. It is worth noting that the PAF is building original active electronically scanned array (AESA) radars.

When reviewing the PAF and PA’s respective capabilities, one can see an apparent demarcation or division of responsibility. For example, the PA’s long-range reach is restricted to around 125 km, but PAF reach extends to 260 km and, potentially, beyond with additional acquisitions.

This could be a sign that the PAF’s air defence responsibilities are strategic in nature, focused on the goal of denying access to Pakistani airspace more so than covering ground assets. If this assessment is accurate, then one can see the PAF delve further into ABM solutions. Besides purchasing a system from China off-the-shelf, the PAF could potentially collaborate with Turkiye on such technology.

Overall, as SAMs take up more of the defensive airpower element, the PAF could gradually steer its fighter aircraft acquisitions towards larger offensive platforms rather than lightweight multirole jets like the JF-17. In other words, the PAF will leverage airpower for strategic outcomes, not tactical gains, at least not as its central objective.

Pakistan Navy’s Air Defence Returns to Form

Since losing the Brooke-class frigate, the PN’s air defence coverages were restricted to point-defence, i.e., defending platforms from low-flying threats and, to a limited extent, incoming anti-ship missiles.

By 2022, however, the PN restored area-wide anti-air warfare (AAW) coverage via four Tughril-class or Type 054A/P multi-mission frigates acquired from China. This was later augmented by the purchase of four Babur-class corvettes from Turkiye.

Currently, the PN will leverage two area-wide SAM systems: the Chinese LY-80 and the Italian-British MBDA CAMM-ER.

Like the LY-80 in use by the Army, the naval variant offers a range of 40 km while using a SARH/INS guidance suite. Each Tughril-class frigate can carry 32 LY-80s via vertical launch system (VLS) cells.

The MBDA CAMM-ER has a stated range of over 40 km, but uses an ARH/INS guidance suite rather than SARH/INS. Like the LY-80, the CAMM-ER is deployable from VLS. The Babur-class corvette will deploy 12 CAMM-ERs via the GWS-26 VLS supplied by Britain.

The PN’s adoption of the CAMM-ER may expand to additional ships. For example, two of its four new Yarmouk-class offshore patrol vessels (OPV) acquired from the Dutch shipbuilder Damen Group were designed to carry VLS for SAMs. The PN is also studying the possibility of upgrading its four F-22P or Zulfiquar-class frigates with the CAMM-ER as well.

Finally, the PN’s original frigate program – the Jinnah-class frigate – is also expected to carry up to 16 CAMM-ERs via the GWS-26 VLS. Reports peg the PN planning for as many as six such frigates.

In terms of short-range capabilities, the PN is preferring to stick with cannon-based CIWS, such as the American Phalanx, Turkish Aselsan Gökdeniz, and Chinese Type 1130. It has not yet adopted newer point-defence missile systems (PDMS) for this role, though several non-American solutions are now available to it, such as the Chinese FL-3000N or Aselsan Levent.

Broadly speaking, the PN could be aiming to build area-wide AAW coverage to better support mixed or composite task forces. For example, it may be planning to deploy task forces consisting of both frigates as well as specialized vessels, like fast attack craft (FAC) and auxiliary ships. Such specialized vessels will generally lack SAMs of their own. Hence, the PN could assign Tughril-class frigates or Babur-class corvettes to provide that protection.

Like the PA, the PN may be aiming to build a measure of airpower capability independent of the PAF, at least in a defensive sense. Once again, it can afford the PN more flexibility in its deployments, while, at the time, freeing the PAF to focus on more strategically-focused tasks, like anti-ship operations against high-value IN targets. This is not to say that the PN would have no PAF protection; rather, the PN and PAF could leverage the latter’s airpower for specific joint air-and-sea operations rather than constantly push PAF fighters to scramble to cover PN ships.

Like the PA, the PAF and PN may have also demarcated areas of responsibility in terms of their AAW coverage. One could see the PN having an actual air defence range limit over 100 km (like the Army), thus opening the possibility of the PN acquiring a long-range SAM for its current or future warships.

Indigenous Initiatives

While each service arm is taking greater ownership of its respective air defence requirements, it should be noted that the PAF, PA, and PN are not planning their work in disconnected silos. To the contrary, it seems that there are several programs ‘gluing’ the tri-service’s air defence efforts into a more cohesive framework.

Unified Sensor Coverage

In 1999, the PAF set out to build a unified radar feed for the tri-services called the ‘Recognized Air and Maritime Picture’ (RAMP). RAMP combines the sensor feeds of both land as well as sea-based radars and the PAF’s airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) aircraft into one view.

By combining these sensor feeds, the RAMP offers a complete picture, one that (in theory) removes the blind spots resulting from relying on strictly one radar source (e.g., using a land-based radar but dealing with gaps due to the blind spots created by the curvature of the Earth).

In building their respective air defence doctrines, each of the tri-services could be using the RAMP to help make their acquisition and deployment decisions. For example, the PA may not need long-range, high-altitude radars as it can leverage the PAF’s AEW&C as well as AN/TPS-77 feeds.

Moreover, as each service arm continues investing in air defence, they will add radar nodes to RAMP. For example, the PN’s surface ships will be equipped with various air and surface surveillance radars, while the PA will keep adding short- and medium-range sensors for its needs. These radars will extend the RAMP’s reach and, potentially, fill additional low-level coverage gaps.

One key aspect of this growth is the development of homegrown original radars. GIDS revealed two such programs, namely, the X-band ‘Multi-Function Air Defence Radar’ (MFADR) and S-band ‘GRAD’ low-to-medium altitude air surveillance radar. It is possible that both platforms are using AESA-based transmit/receive modules (TRM), making them modern and potentially capable systems.

The GRAD will have a range of 100 km against targets with radar cross-sections (RCS) of 1m2, i.e., relatively small objects, such as drones. The range of the MFADR was not revealed, but Pakistan is likely developing it to accompany its homegrown SAM programs, such as the LoMADS, which offer a range of up to 100 km. Thus, the MFADR may have a range of 100-150 km.

The development of original radars and local production would suggest that each of Pakistan’s service arms wants to intensify air defence investment. In other words, there is enough of a long-term domestic requirement for radars to justify their production at home.

Homegrown Surface-to-Air Missiles

In addition to radars, the Pakistani industry is also developing at least two SAM platforms: the LoMADS and the FAAZ-SL-series. The LoMADS is expected to provide a range of 7-100 km, while FAAZ SL will have a range of 20-25 km. Both systems may use the MFADR as a surveillance and targeting radar.

While the specifications of LoMADS and FAAZ-SL are modest compared to the cutting-edge SAMs in production in other parts of the world, including India, they are crucial programs. The LoMADS and the FAAZ-SL will give Pakistan a technology platform to build upon through the long-term. For example, it can use these programs to develop competency in dual-pulse rockets, solid fuel composition, airframe materials, and missile design and testing, which can translate into longer-ranged SAMs in the future.

Both the LoMADS and FAAZ-SL also appear to be designed for workhorse requirements across each of the tri-services. For example, the LoMADS is an area-wide solution, so it can be adopted by each of the PAF, PA, and (if a VLS is developed) the PN. Basically, the goal of the LoMADS could be to induct it in numbers, thereby justifying the overhead costs of developing and producing it locally.

Likewise, the FAAZ-SL is a SHORAD solution that will use an indigenous AAM as its missile. Not only would the FAAZ-SL support the low-level needs of each service arm, but by reusing the FAAZ AAM, it seems that the goal is to standardize as much as possible. Basically, the PAF could use a single type of missile for both its air-to-air and surface-to-air needs, thereby simplifying production and generating more yield from the overhead of developing and producing this missile.

C-UAS Systems

The Pakistani industry is working on at least one counter-unmanned aerial system (C-UAS) solution. Certain UAS threats involve drone swarms and low-cost loitering munitions that are difficult to defend against with SAMs. Hence, these threats require more scalable solutions, like electronic warfare (EW) and directed energy weapons (DEW).

In terms of EW-based C-UAS, a state-owned Pakistani vendor is developing a system with “cognitive software defined radio (SDR)” technology. This ‘cognitive SDR’ technology is being used to give the C-UAS a means to interfere with the radio frequencies and satellite navigation systems used by UAS threats, like swarming drones, for example.

The PAF also revealed that it was working on DEW solutions, namely high-energy laser (HEL) and high-powered microwave (HPM) systems. It is not known if the PAF is procuring these off-the-shelf from China or Turkiye, or developing them in-house.

Industry Opportunities

While localized air defence solutions are a goal, the Pakistani military’s near-term acquisitions will primarily be driven by imports. Currently, China has taken up the bulk of Pakistan’s SAM purchases, while Europe and the United States have split Pakistan’s radar needs.

While cost plays a role, it may not be the deciding factor. For example, when it comes to radars, the PAF and the PN have shown a willingness to buy American and Western European systems. These include the Lockheed Martin TPS-77 MRR, a Hensoldt update kit for the MPDRs, and a new batch of Saab Erieye AEW&C platforms, among others. Thus, for the foreseeable future, Western vendors will likely have considerable opportunity in the PAF and PN’s respective radar requirements.

It is more difficult for Pakistan to acquire Western SAMs at scale. In the case of the PAF’s strategic or territorial defensive needs, the requirement is for a sophisticated system. Such solutions are either too cost prohibitive for Pakistan to acquire in sufficient numbers, or simply unavailable due to regulatory or security concerns. Hence, when it comes to strategically valuable SAMs, Pakistan will likely seek such solutions from China or, potentially, collaborate with Turkiye to develop an original system.

In some scenarios, however, Pakistan could be predisposed to acquiring Western SAMs. This would be in the case of the PN. The growth of its air defence needs will not result in as many SAM units as the PA or PAF require. Currently, for example, the PN’s CAMM-ER needs are limited to four MILGEM corvettes with the possibility of configuring up to six additional vessels (i.e., two Yarmouk-class OPVs and four Zulfiquar-class frigates). Each of these vessels would carry eight to twelve VLS cells.

Thus, the quantitative scale of the PN’s requirements are not as extensive as those of the PA or PAF, hence it can invest in Western SAMs. This is why the forthcoming MBDA CAMM-MR (range: 100 km) could become an option for the PN. For example, the PN may seek a pair of dedicated AAW frigates for commanding its task-forces and providing greater area-wide air defence coverage. These frigates would likely carry 32 to 64 VLS cells and, in turn, contain a mix of both medium-range and long-range SAMs. While individually expensive, the CAMM-MR would not be the main cost driver of such ships, nor would their omission necessarily result in a significant savings for the PN as the quantity it would look for is much smaller compared to a potential PA or PAF requirement.

Regarding the long-term, the emergence of homegrown SAMs could displace foreign suppliers, but only for complete solutions. Pakistan is not an industrialized country, which prevents it from sourcing every critical input of a missile through indigenous means. It will still require foreign support to set up production facilities and for sourcing certain critical inputs, especially electronics for guidance suites. Likewise, Pakistan will likely source the TRMs for homegrown AESA radars from foreign suppliers.

While it cannot indigenize completely, Pakistan’s goal with domestic production is to leverage some of its other advantages, such as lower labour costs and, potentially, partial indigenous sourcing for things like solid fuels and rocket motors. For the quantitatively-heavy requirements of the PAF and PA, partial domestic production could help Pakistan control its costs.