2791Views 0Comments

Pakistan Navy MILGEM Program: Babur-Class Corvette

Editor’s note (07 December 2024): This post was updated with details on the finalized configuration and ongoing induction of Pakistan’s MILGEM / Babur-class corvettes.

On 05 July 2018, the Pakistan Ministry of Defence Production (MoDP) signed a deal with Turkey’s Military Factory and Shipyard Corporation (ASFAT A.Ş.) for the purchase of four customized MILGEM Ada corvettes for the Pakistan Navy (PN).[1] The PN is slated to receive all four ships by 2025, with the first due in 2023.[2]

With a reported value of $1.5 billion US, the MoDP acquired more than four new ships, but also “complete transfer of technology and the transfer of intellectual property (IP) rights for the design of these ships.”[3]

Though ‘technology transfer’ is not new to Pakistan, the MILGEM will differ from past projects as it will see ASFAT A.Ş. assist its Pakistani counterparts – i.e., Karachi Shipyard & Engineering Group (KSEW), Navy Research and Development Institute (NRDI), etc – design Pakistan’s “first indigenously designed and constructed frigate.”[4] In other words, with the conclusion of the MILGEM, Pakistan should gain the ability to design and construct modern frigates without OEM-supplied prefabricated kits-of-materials (KoM).

As of December 2024, the PN commissioned the lead ship, PNS Babur (F280). It is also currently testing the remaining three ships – PNS Badr (F281), PNS Khyber (F282), and PNS Tariq (F283).

This article will shed more light on this transfer-of-technology (ToT) and joint-design agreement as well as details on the intended configuration and weapons of the PN MILGEM, or Jinnah-class corvettes/frigates.

Background: MILGEM / Ada-Class Corvette

The MILGEM (short for Milli Gemi – or “National Ship”) is Turkey’s indigenous corvette program. In 2006, Turkey’s Undersecretariat for Defence Industries (SSM) awarded STM Savunma Teknolojileri Mühendislik ve Ticaret A.Ş. (STM) to take lead as the main contractor for the development of the corvette program.[5]

The MILGEM started as a corvette with a displacement of 2,300-2,400 tons, length of 99.50 m, and beam of 14.40 m. It would offer a maximum speed of 29 knots, and an economical cruising speed of 15 knots. It would have a total endurance of 3,500 nm at 15 knots by using a on a combined diesel-and-gas (CODAG) system for propulsion. It would also have an aft deck and hangar for a medium-weight naval helicopter.

The first iteration of the MILGEM – i.e., the Ada-class – is an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) corvette with anti-ship warfare (AShW) and a short-range air defence (SHORAD) capabilities, the latter coming through in the form of the RIM-116 Rolling Airframe Missile (RAM). Initially, these ships were to draw on off-the-shelf weapon systems from the United States, such as the RGM-84 Harpoon anti-ship missile (AShM) and Mk. 46 lightweight ASW torpedoes. But with its future ships, Turkey opted to rely on its own munitions.

Istanbul Naval Shipyard (INSY) began constructing the first MILGEM Ada in January 2007. Designated TCG Heybeliada (F-511), the ship began its sea trials in September 2008. The Turkish Navy commissioned the TCG Heybeliada in September 2011. Turkey commissioned the remaining three corvettes – i.e., TCG Büyükada (F-512), TCG Burgazada (F-513), TCG Kınalıada (F-514) – from 2011 to 2019.

The second iteration of the MILGEM is the Istanbul-class frigate. This design features a lengthened hull – i.e., 113-114 m versus the Ada-class’ 99.50 m – for a vertical-launch system (VLS) at the bow. The Istanbul-class frigate would also displace at 3,000 tons, i.e., 600+ tons more than the Ada-class. Construction of the first Istanbul-class frigate began in January 2017. The Turkish Minister of Defence at the time, Fikri Işık, stated that Turkey was sourcing over 65% of the MILGEM’s inputs domestically by that point.[6] According to Turkey’s state-owned media, the lead ship was nearing completion in 2020.[7]

The third variant is the TF-2000, an anti-air warfare (AAW) destroyer. Its exact specifications are not clear at this stage, but it is expected to be a large vessel with up to 64 VLS cells.[8] It will house Turkey’s indigenous ÇAFRAD X-band multifunction phased array radar and, possibly, its long-range surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems (it is currently working on two projects: HISAR-U and SIPER).

The contract with Pakistan resulted in a sub-variant of the MILGEM Ada-class corvette. Based on the image/impression shown during the first ship’s steel cutting ceremony, the PN’s ships are largely the same as the Ada-class, except they also include a 12-cell VLS system at the bow. In a sense, the MILGEM for Pakistan can be the fourth variant, though it is more of a side or lateral branch-out from the Ada-class than a vertical development like the Istanbul-class or TF-2000. It is unclear if the fourth ship – i.e., the first designed in Pakistan – will be a continuation of the Ada-class with VLS, or a new design entirely.

Interestingly, STM had also designed two other sub-variants of the MILGEM, both for export. The first was STM’s proposal for Brazil’s Tamandaré Class Corvette (CCT) bid. The STM CCT concept was longer than the Ada-class (103.4 m versus 99.50 m), and it included an eight-cell VLS inserted to the bow. It also displaced at 2,970 tons, i.e., 500-600 tons more than the displacement of the Ada-class. The second variant/concept was the CF3500, which STM submitted for Colombia’s Plataforma Estratégica de Superficie (PES) bid. The CF3500 displaced substantially more than the Ada-class at 3,500 tons, and included a VLS at the bow.

However, the PN MILGEM’s design work was undertaken by a different main contractor, ASFAT A.Ş. So, if ASFAT A.Ş. transfers the design and intellectual property (IP) of this ship to Pakistan, the MILGEM will have at least three different parties carrying its core design work – and across six or seven different variants.

Timeline of Acquisition

The Pakistan Navy (PN) first expressed interest in the MILGEM in 2006, i.e., since the start of the corvette’s development. However, the PN was unable to commit to a purchase at the time due to a lack of funds – in fact, the PN had shelved a number of programs at the time, including the purchase of three Type 214 air-independent propulsion (AIP)-equipped submarines from Germany, among others.

Negotiations for the MILGEM restarted in 2015.[9] However, news of the PN’s renewed interest in the ships broke in 2016 during the official visit of Turkey’s then Minister of Defence, Fikri Işık, to Pakistan. According to Işık, Pakistan was interested in acquiring four MILGEMs. In 2016, Quwa had also suggested that Pakistan could seek a sub-variant of the MILGEM Ada-class with VLS, which actually became a reality in 2018.

2016-2018: Negotiations

Originally, the expected cost of the PN MILGEM program was around $1 billion US. In 2017, Pakistan was negotiating with STM. STM’s general manager at the time, Davut Yılmaz, said that the Pakistani MILGEM would come at a “lower than normal price” because it would eschew weapons from the original Ada-class configuration. Instead, the PN was to source its own weapons. However, there was no mention of design changes or VLS, suggesting that the PN’s original plan for the MILGEM was for an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) and anti-ship warfare (AShW)-capable ship, but with limited anti-air warfare (AAW).

At some point in 2017 or 2018, the PN moved away from STM, and began engaging ASFAT A.Ş. – a different main contractor. In July 2018, the Pakistan Ministry of Defence Production (MoDP) signed a contract for four MILGEM ships with ASFAT A.Ş. In contrast to the STM contract, the contract with ASFAT A.Ş. swelled to $1.5 billion US, i.e., a 50% increase to the original estimate.[10] The main causes for the cost increase were likely the addition of VLS to the Ada-class and the transfer of intellectual property (IP) to Pakistan.

In 2017, the PN also signed a contract with Damen Shipyards Group for two 2,300-ton corvettes based on an offshore patrol vessel (OPV) design. Basically, the PN selected an OPV built to commercial specifications (i.e., comparatively lower cost), but with the aim of arming them with anti-ship missiles (AShM) as well as electronic support measures (ESM) and electronic intelligence (ELINT) equipment.

Interestingly, the OPV-based corvettes – designated Yarmouk-class – deliver the same mission capabilities as the baseline Ada-class, but at a much lower cost. Yes, the Yarmouk-class corvettes lack ASW, but Damen Shipyards’ OPV designs have space for mission modules, so the PN might be able to add ASW.

Thus, the PN likely settled its original corvette requirement through Damen Shipyards Group, and in turn, opted to revise and expand the MILGEM into a program for the PN’s long-term requirements.

2023-2025: Scheduled Deliveries

The first MILGEM is scheduled for completion within 54 months of the program starting (i.e., in May 2019), with the next three slated for 60, 66 and 72 months of the project start.

The PN is to receive its first two MILGEM ships in 2023, and the last two by 2025.[11][12][13] Two of the ships will be built in Turkey, while the other two will be built in Pakistan by Karachi Shipyards & Engineering Works (KSEW). Istanbul Shipyard cut the steel of the first PN MILGEM in September 2019.

Pakistan's MILGEM is a Custom Design

The PN’s MILGEM program certainly involves a custom design of the ship, i.e., one that includes VLS for a surface-to-air missile (SAM) system. However, it is unclear if the design changes apply to all four ships, or only the fourth ship. The fourth ship is significant because ASFAT A.Ş. will help its Pakistani counterparts – i.e., KSEW and NRDI – to design the vessel as Pakistan’s first in-house frigate program.

That said, in the steel-cutting ceremony of the first ship, the official impression of the ‘PN MILGEM’ shows a design with a 16-cell VLS at the bow. So, it seems that the VLS is a standard feature across all MILGEMs meant for the PN (since there is no reason to show the design of the final ship to represent the first ship).[14] KSEW also released its own illustration of the PN MILGEM. It differs in some respects from the one INSY had showed, but it still retains the VLS.

Photo source: ASFAT A.S

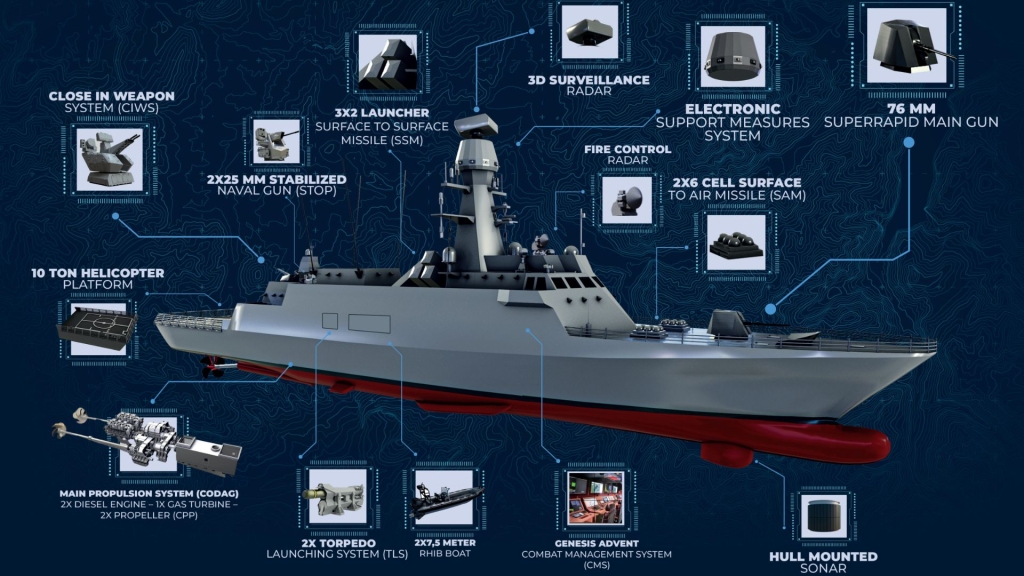

Specifications

- Length: 108.2 m

- Width: 4.8 m

- Draught: 4.1 m

- Displacement: 2,985 tons

- Speed: 26+ knots

- Range: 3500 nautical miles

- Endurance: 15 days

- Crew: 93 + 40

- Propulsion: CODAG via two diesel engines and one gas turbine

Weapon Systems

The PN MILGEM will be armed with a 76 mm main gun, though the make or model are unknown. It could be the Leonardo Super Rapid, which is also equipped on the Ada-class. However, this was not confirmed.

Anti-ship cruising missile (ASCM) configuration of the Babur-class corvette involves two three-cell launchers carrying the GIDS Harbah ASCM. While the range of the Pakistan Navy’s (PN) Harbah ASCM was not disclosed, the export variant can reach up to 280 km. The PN uses the Harbah as a dual-anti-ship and land-attack missile.

Anti-Ship Warfare

It is unclear if the PN will arm its MILGEMs with the RGM-84 Harpoon anti-ship cruising missile (ASCM) – the US may not allow it (note: the US also did not allow the PN to arm its MRTP-33 fast attack crafts with the Harpoon). The Roketsan Atmaca ASCM may be an option, but the PN does not need it.

The PN MILGEM will use the locally produced Harbah dual-ASCM and land-attack cruise missile (LACM). Pakistan did not disclose the actual range of the Harbah, but the export version can reach up to 290 km. If modelled on the Babur-3 submarine-launched cruise missile (SLCM), the Harbah could have a range of 450 km.

The anti-air warfare (AAW) configuration of the Babur-class corvette involves a 12-cell vertical launch system (VLS) armed with the MBDA CAMM-ER/Albatros NG surface-to-air missile (SAM) system. The Albatros-NG has a range of over 45 km.

Anti-Air Warfare

In terms of anti-air warfare (AAW), the PN MILGEM will differ from the Ada-class in two key areas:

First, the PN MILGEM eschews the RIM-116B (Block 1A) Rolling Airframe Missile (RAM) in favour of the Aselsan Gökdeniz close-in-weapon-system (CIWS). The RAM would have required US approval, but the PN also seems to prefer CIWS-based solutions for point-defence.[15] It chose a similar Chinese CIWS system for the Type 054A/P frigate, i.e., the Type 730 (instead of the missile-based FL-3000).

The Aselsan Gökdeniz uses twin 35-mm gun-barrels that can fire 1,100 rounds per minute. The end-user can arm the guns with both airburst and high-explosive incendiary ammunition. Leveraging an integrated tracking radar, the Gökdeniz can track targets automatically and operate autonomously.

Second, the PN MILGEM was to have two eight-cell vertical launch systems (VLS), which can house medium-range surface-to-air missiles (SAM).[16] The PN Chief of Naval Staff (CNS), Admiral Zafar Mahmood Abbasi, stated the PN MILGEM will be armed with the Chinese LY-80, which offers a range of 40 km (there is also a newer variant with a range of 70 km).[17] The PN will also equip its Type 054A/P frigates with the LY-80.

However, the LY-80 is not a guarantee. In October 2019, the CEO of MBDA Italy visited Pakistan and met with the PN CNS. MBDA Italy could certainly have offered its own AAW solution to the PN, potentially the Common Anti-Air Modular Missile (CAMM) or CAMM-ER. Interestingly, Pakistan had reportedly expressed interest in the CAMM-ER.[18] The CAMM-ER offers a range of over 45 km.

Finally, the PN was reportedly working on an in-house ‘air defence missile project’ as well.[19] This was the only time the PN was quoted revealing such a project. However, it would not be surprising seeing the PN’s interest in undertaking original design, engineering and integration work, which is evident in the MILGEM, next-generation long-range maritime patrol aircraft (LRMPA) program, and miniature submarine project.

In any case, the PN MILGEM will not have difficulty deploying any of these SAM types. In addition to the VLS in the bow, the combat management system (CMS) supplier, Havelsan, said it will modify its suite to enable custom weapons integration.[20] The PN will also get integration know-how from Turkey.[21]

Ultimately, the PN selected the MBDA CAMM-ER and, in turn, configured its MILGEM corvettes with a 12-cell VLS system to deploy those SAMs.

Anti-Submarine Warfare

The PN MILGEM’s anti-submarine warfare (ASW) capability will likely come in the form of two triple-cell lightweight 324 mm torpedo launchers. It is unclear if the PN would use the Mk.48 torpedo, or alternative lightweight torpedoes from Turkey, Italy or China. The PN is not short of options in terms of torpedoes.

Subsystems

The PN MILGEM’s subsystem configuration is similar to that of the Ada-class.

Main Search Radar

The PN MILGEM will use the Thales SMART-S Mk2 as its main radar, but this will likely be the version built by Aselsan. The S-band radar offers a range of up to 250 km.[22]

Combat Management System

In terms of combat management system (CMS), the PN MILGEM will use the Havelsan ADVENT.[23] Havelsan introduced the ADVENT in 2019 and markets it as a “new generation command and control system that responds to the needs of a force-oriented, network-supported operational approach.”[24]

In addition to enabling for the integration and management of various weapon systems, the ADVENT will allow the PN MILGEM to operate in a network-enabled environment. In this respect, its key feature is the ability to support multiple data-link protocols, be it across surface warships, aircraft, and other platforms.

The PN’s main network environment is the Naval Information Exchange System (NIXS), which was developed by the Turkish company MilSoft. The PN also uses its own data-link protocol – i.e., ‘Link Green’ – but NIXS likely draws on other protocols too. The PN operates US and European equipment and interoperates with PAF assets, such as the Karakoram Eagle airborne early warning and control system.

Electronic Support Measures

The PN MILGEM’s primary electronic support measures (ESM) suite is the Aselsan ARES-2NC, a variant of the ESM the PN will use from its Agosta 90B submarines.[25]

Like the Agosta 90Bs, the PN MILGEM will have the capacity to monitor and record transmissions on the electromagnetic spectrum, i.e., passively track radar and other signals from India and, in turn, build-out Pakistan’s threat library for electronic warfare (EW) jamming.

However, the ARES-2NC will go a step further by enabling the PN MILGEM to engage in EW activities. The ship will have digital radio frequency memory (DRFM)-based arrays to direct radar frequency (RF) jamming and other disruptive/mitigation activities.[26]

Other Subsystems

Meteksan Defence will supply the PN MILGEM with its Yakamos hull-mounted sonar system. The Yakamos operates on a 7.5kHz band with active and passive detection modes. It offers a detection range of 30 km.[27]

The PN MILGEM will also deploy Aselsan’s HIZIR torpedo countermeasure system. The HIZIR is a complete suite consisting of a towed array, decoy array and expendable decoys. The decoys can transmit an acoustic signal emulating the characteristics of the ship.[28]

Transfer-of-Intellectual Property

According to official statements, the PN MILGEM contract includes “complete transfer of technology” and “transfer of intellectual property rights for the design of these ships.”[29] In addition, ASFAT A.Ş. will assist its Pakistani counterparts to ‘jointly design and construct’ the fourth ship.[30]

There are three major components to the contract.

First, ‘transfer-of-technology’ (ToT), which likely refers to equipping KSEW to construct two of the four ships. In terms of naval programs, ToT of this nature is not new to Pakistan as it built the Agosta 90B submarine, Azmat-class fast attack craft (FAC), F-22P frigate and 17,000-ton fleet tanker were built under license. However, for each of these programs Pakistan had relied on original equipment manufacturer (OEM)-supplied material kits. These ‘ToT’ measures did not give Pakistan the capacity to manufacture these ships independently of the OEM, which still held onto the rights and knowhow of the design.

Second, which is a significant break from past naval contracts, the PN MILGEM deal involves the “transfer of intellectual property rights for the design of these ships.” Now, in contrast to the Agosta 90B and other past deals, Pakistan will retain the knowhow of the design and its rights. In other words, not only could it freely manufacture ships beyond the current contract, but also modify it in a multitude of ways. It can, for example, change the weapon suite, propulsion, steel, superstructure materials, electronics and more.

So, the intellectual property rights transfer and capacity building for design will allow Pakistan to construct additional ships of this line as well as alter them. The latter is also key in that Pakistan will gain the ability to choose input suppliers, thereby having more control of the cost.

Third, ASFAT A.Ş. will assist Pakistan in designing an original frigate. In 2018, a PN official said the fourth ship will be “the first Jinnah-class frigate,” but Turkish defence media have indicated the entire line of ships are of the Jinnah-class.[33][34] However, either way, the fourth ship will be different from the first three vessels. In October 2020, the PN CNS confirmed that the Jinnah-class frigate will actually be a new line of ships separate of the four modified corvettes.

According to official statements, the PN MILGEM contract includes “complete transfer of technology” and “transfer of intellectual property rights for the design of these ships.”[29] In addition, ASFAT A.Ş. will assist its Pakistani counterparts to ‘jointly design and construct’ the fourth ship.[30]

There are three major components to the contract.

First, ‘transfer-of-technology’ (ToT), which likely refers to equipping KSEW to construct two of the four ships. In terms of naval programs, ToT of this nature is not new to Pakistan as it built the Agosta 90B submarine, Azmat-class fast attack craft (FAC), F-22P frigate and 17,000-ton fleet tanker were built under license. However, for each of these programs Pakistan had relied on original equipment manufacturer (OEM)-supplied material kits. These ‘ToT’ measures did not give Pakistan the capacity to manufacture these ships independently of the OEM, which still held onto the rights and knowhow of the design.

Second, which is a significant break from past naval contracts, the PN MILGEM deal involves the “transfer of intellectual property rights for the design of these ships.” Now, in contrast to the Agosta 90B and other past deals, Pakistan will retain the knowhow of the design and its rights. In other words, not only could it freely manufacture ships beyond the current contract, but also modify it in a multitude of ways. It can, for example, change the weapon suite, propulsion, steel, superstructure materials, electronics and more.

So, the intellectual property rights transfer and capacity building for design will allow Pakistan to construct additional ships of this line as well as alter them. The latter is also key in that Pakistan will gain the ability to choose input suppliers, thereby having more control of the cost.

Third, ASFAT A.Ş. will assist Pakistan in designing an original frigate. In 2018, a PN official said the fourth ship will be “the first Jinnah-class frigate,” but Turkish defence media have indicated the entire line of ships are of the Jinnah-class.[33][34] However, either way, the fourth ship will be different from the first three vessels. In October 2020, the PN CNS confirmed that the Jinnah-class frigate will actually be a new line of ships separate of the four modified corvettes.

The Basis of a Next-Generation Frigate?

The end outcome of the PN MILGEM project is to design and construct an indigenous frigate – this frigate will likely be the basis of Pakistan’s next-generation, mainstay warship. Thus, Pakistan would aim to gradually build its surface fleet through this design.

Get the Latest Pakistan Navy News

March 17, 2025

January 20, 2025

January 13, 2025

December 29, 2024

News Updates

29 September 2019: On Sunday, 29 September 2019, Istanbul Shipyard conducted the steel-cutting ceremony of the first MILGEM corvette slated for the Pakistan Navy. | Read More.

14 November 2019: Aselsan announced that it signed a €176.9 million contract with ASFAT A.Ş to produce and supply electronics for the PN’s MILGEM corvettes. | Read More.

04 June 2020: Istanbul Naval Shipyard (INSY) lays keel for Pakistan’s first MILGEM corvette/frigate. | Read More.

09 June 2020: Karachi Shipyard & Engineering Works (KSEW) cuts steel for second PN MILGEM. | Read More

06 October 2020: General Electric (GE) signs a contract to supply the LM2500 marine gas turbine system for use on the PN’s MILGEM.[35]

25 October 2020: KSEW laid the keel for the second MILGEM. This is the first of two ships under construction in Pakistan. This particular ship is due for delivery by the early half of 2024.[36]

30 April 2021: INSY laid the keel of the PN’s third MILGEM corvette.

15 August 2021: INSY launched the PN’s first MILGEM corvette for sea trials, the PNS Babur.

06 November 2021: KSEW lays the keel for the fourth and final PN MILGEM corvette.

20 May 2022: KSEW launched the PN’s third Babur-class corvette, PNS Badr, for trials.

02 August 2023: KSEW launched the fourth corvette, PNS Tariq, for sea trials.

23 September 2023: The PN commissions the lead ship, PNS Babur, at INSY.

06 September 2024: The PNS Babur joins the PN fleet in Pakistan.

[1] Press Release. “Pakistan Navy Signed Contract for Acquisition of 4x MILGEM class warships with Turkey.” Press Information Department. Ministry of Information. Government of Pakistan. 05 July 2018. URL: http://pid.gov.pk/site/press_detail/8782

[2] İbrahim Sünnetci. ““Together for Peace” AMAN-19 Multinational Naval Exercise & Pakistan – Turkey Defence Cooperation.” Defence Turkey. Volume 13. Issue 91.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Press Release. “Pakistan Navy Signed Contract for Acquisition of 4x MILGEM class warships with Turkey.” Press Information Department. Ministry of Information. Government of Pakistan. 05 July 2018. URL: http://pid.gov.pk/site/press_detail/8782

[5] “Acquisition of Design Services and Platform Construction and Outfitting Equipment for MILGEM Project Prototype Ship and Second Ship.” Undersecretariat for Defence Industries. Government of Turkey. URL: https://web.archive.org/web/20110722083305/http://www.ssm.gov.tr/home/projects/naval/Warship/Sayfalar/AcquisitionofDesignServices.aspx

[6] “Construction of the first national frigate TCG Istanbul started.” Deniz Haber Ajansi. 19 January 2017. URL: https://www.denizhaber.net/ilk-milli-firkateyn-tcg-istanbulun-insasina-baslandi-haber-72209.htm

[7] Goksel Yildirim. “Shareholders continue work to complete vessel project in short period.” Anadolu Agency. 20 February 2020. URL: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/economy/turkeys-first-frigate-project-nears-end/1739845

[8] ÇAFRAD: Multi-Purpose Phased Array Radar. Presidency of Defence Industries (SSB). URL: https://www.ssb.gov.tr/Website/contentList.aspx?PageID=1264&LangID=1

[9] Interview with STM General Manager Murat İkinci. Defence Turkey. Volume 14. Issue 95. 2019. URL: https://www.defenceturkey.com/en/content/stm-s-naval-expertise-propelling-export-oriented-development-and-collaboration-projects-with-the-turkish-defence-industry-3635

[10] İbrahim Sünnetci. “Together for Peace” AMAN-19 Multinational Naval Exercise & Pakistan – Turkey Defence Cooperation.” Defence Turkey. Volume 13. Issue 91. 2019. URL: https://www.defenceturkey.com/en/content/together-for-peace-aman-19-multinational-naval-exercise-pakistan-turkey-defence-cooperation-3454

[11] “Turkey to sell 4 corvettes to Pakistan Navy in largest single military export deal.” Anadolu Agency (via The Daily Sabah). 05 July 2018. URL: https://www.dailysabah.com/defense/2018/07/05/turkey-to-sell-4-corvettes-to-pakistan-navy-in-largest-single-military-export-deal

[12] “Signatures signed for the sale of 4 MILGEM Corvettes to Pakistan.” Military Factory and Shipyard Corporation (ASFAT A.Ş.). URL: https://www.asfat.com.tr/pakistana-4-milgem-korvetinin-satisinda-imzalar-atildi/

[13] İbrahim Sünnetci, “A Look at Latest Status of the PN MILGEM Project.” Defence Turkey. Volume 14. Issue 97. 2019: URL: https://www.defenceturkey.com/en/content/a-look-at-latest-status-of-the-pn-milgem-project-3824

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] “Italy Restores Funding for CAMM ER Air-Defense Missiles.” Defense-Aerospace. 21 June 2019. URL: https://www.defense-aerospace.com/article-view/release/203698/italy-restores-funding-for-camm-er-air_defense-missile.html

[21] Usman Ansari. “Pakistan test-fires indigenous anti-ship missile.” Defense News. 05 January 2018. URL: https://www.defensenews.com/naval/2018/01/05/pakistan-test-fires-indigenous-anti-ship-missile/

[22] İbrahim Sünnetci. “Together for Peace” AMAN-19 Multinational Naval Exercise & Pakistan – Turkey Defence Cooperation.” Defence Turkey. Volume 13. Issue 91. 2019. URL: https://www.defenceturkey.com/en/content/together-for-peace-aman-19-multinational-naval-exercise-pakistan-turkey-defence-cooperation-3454

[23] İbrahim Sünnetci, “A Look at Latest Status of the PN MILGEM Project.” Defence Turkey. Volume 14. Issue 97. 2019: URL: https://www.defenceturkey.com/en/content/a-look-at-latest-status-of-the-pn-milgem-project-3824

[24] Ibid.

[25] İbrahim Sünnetci, “A Look at Latest Status of the PN MILGEM Project.” Defence Turkey. Volume 14. Issue 97. 2019: URL: https://www.defenceturkey.com/en/content/a-look-at-latest-status-of-the-pn-milgem-project-3824

[26] Havelsan: https://www.havelsan.com.tr/sektorler/savunma-ve-guvenlik/deniz/su-ustu-savas-yonetim-sistemleri/havelsan-advent

[27] İbrahim Sünnetci, “A Look at Latest Status of the PN MILGEM Project.” Defence Turkey. Volume 14. Issue 97. 2019: URL: https://www.defenceturkey.com/en/content/a-look-at-latest-status-of-the-pn-milgem-project-3824

[28] Aselsan: https://www.aselsan.com.tr/NEWS_Naval_Electronic_Warfare_EW_Suite_1873.pdf

[29] Meteksan Defence: https://www.defence-industries.com/products/meteksan-savunma-sanayii/yakamos-hull-mounted-sonar

[30] Aselsan: https://www.aselsan.com.tr/en/capabilities/naval-systems/torpedo-and-torpedo-countermeasure-systems/hizir-torpedo-countermeasure-system-for-surface-ships

[31] Press Release. “Pakistan Navy Signed Contract for Acquisition of 4x MILGEM class warships with Turkey.” Press Information Department. Ministry of Information. Government of Pakistan. 05 July 2018. URL: http://pid.gov.pk/site/press_detail/8782

[32] Ibid.

[33] Qoumi Awaz News: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tdy5Vh9EW6w&feature=youtu.be&t=66

[34] İbrahim Sünnetci, “A Look at Latest Status of the PN MILGEM Project.” Defence Turkey. Volume 14. Issue 97. 2019: URL: https://www.defenceturkey.com/en/content/a-look-at-latest-status-of-the-pn-milgem-project-3824

[35] Press Release. “GE Signs Contract to Provide STM with LM2500 Gas Turbines to Power Pakistan Navy’s New MILGEM Corvettes.” 06 October 2020. URL: https://www.geaviation.com/press-release/marine-industrial-engines/ge-signs-contract-provide-stm-lm2500-gas-turbines-power

[36] “Keel laying of MILGEM Class Corvette for Pakistan Navy held.” Associated Press of Pakistan. 25 October 2020. URL: https://www.app.com.pk/national/keel-laying-of-milgem-class-corvette-for-pakistan-navy-held/