24 September 2015

By Bilal Khan

The past several weeks have seen Russia rapidly bolster its military presence in Latakia, Syria’s coastal western region and one of Bashar al-Assad’s remaining strongholds. Latakia is considered the heartland of Syria’s Alawite minority and the core of Bashar’s internal support.

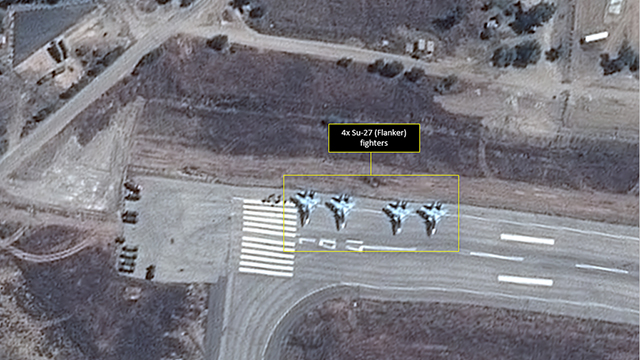

This month we have seen Russia deploy as many as 28 combat aircraft: 12 Su-24 fighter-bomber aircraft, 12 Su-25 close air support and ground attack aircraft and 4 Su-30M multi-role fighters. In addition, it has also reportedly sent 20 helicopters. Overall, this is not exactly a ‘small’ force, especially in terms of the apparent ground attack capability being built in Syria.

That said, it would be premature to suggest that the Russian military buildup in Syria is an indication of Moscow’s willingness to engage in fighting in that country. In fact, the U.S itself seems to think that Russia’s deployments in Syria are for maintaining a presence more than for fighting. For example, U.S Secretary of State John Kerry said, “It is the judgment of our military and most experts that the level and type represents basically force protection, a level of protection for their deployment to an air base given the fact that it is in an area of conflict.” (Financial Times). In other words, Russia wants to maintain a physical presence in Syria, and the weapons it is sending there for use by its forces are likely intended to defend that presence, not necessarily weaken the capacities of others, including groups such as Jabhat an-Nusra, ISIS and others.

But it is worth noting however that Russia is apparently looking to ensure that it has a dense presence in Syria. For example, Jane’s noted that in addition to the airport in Latakia, the Russians were building two additional bases in the country, one 7km north of Latakia and the other 3km to the west (Reuters). Jane’s also noted that it is possible that the Russians could deploy as many as 1,000 military personnel at the airport alone (IHS Jane’s 360). Overall, the Russians are entrenching themselves within Syria quite firmly, essentially making them an actor to deal with in any scenario involving Bashar or his regime.

A well-entrenched presence and a resulting seat on any post-war discussion on Syria are the most likely objectives behind the Russian military buildup in Syria. Why this and not something more decisive, such as action against ISIS? To answer that, it would be a good idea to study the nature of Moscow’s ties with Damascus.

Understanding Russian-Syrian Ties

The root of Russian-Syrian ties is that of defence, particularly commercial transactions and technical support. While it is true that the Russians have been the modern Syrian state’s most prominent supplier of arms, it would be inaccurate to suggest that those arms sales translated into complete political influence in Damascus or unflinching support for Bashar and his regime. Russia is at heart a regional power, it is concerned about its borders first and foremost; issues in more distant lands, such as the Middle East, are generally an outer concern compared to the affairs of Russia’s direct neighbours. Just review the commitment of Moscow to the issues of the Middle East versus Ukraine to see the difference in the resources allocated to addressing each concern.

That said, if it feasibly could, Moscow might look into building a presence in distant lands, especially if it means using that presence as leverage to strengthening its position on more immediate (i.e. border) issues. A prime example (before the recent surge) of this is the Tartus naval base. The Tartus base, if brought to its envisioned potential, could enable the Russians to station major naval assets in the Mediterranean Sea, right near the doorsteps of Western Europe (i.e. NATO). But despite the potential, the Russians did not exactly invest a lot into Tartus in recent years, leaving it to be just that, potential, not a presence (BBC). If Russia were to extend itself into a distant front like the Middle East, then it would do so for drastic and decisive reasons, not as part of some routine foreign relations calculus.

Besides symbolic elements such as Tartus, the balance of Russia’s presence in Syria is composed of servicing lucrative defence contracts, such as with the Syrian Arab Air Force (SyAAF). In 2007-2009 the Syrians reportedly ordered Yak-130 advanced jet trainers, MiG-29M/M2 multi-role fighters and MiG-31 high-altitude interceptors, but the ongoing civil war has meant – until possibly very recently – that these aircraft would be on hold in Moscow until the fighting in Syria ends (Defence Industry Daily). In the absence of a crisis (such as the civil war), the Russians would maintain personnel in Syria to assist the Syrian forces in integrating and servicing their new weapon systems.

While this could theoretically serve as a gateway for political influence in Damascus, it does not always translate as such (besides maybe directing decision-makers to more Russian arms). In the case of Syria, the Russians (counter to what one might hear amongst many analysts and pundits) does not have significant political influence. Remember, Syria is a distant land to Russia, and we have seen (with the efforts of the U.S in Afghanistan/Iraq and Russia in Ukraine) the amount of resources it takes to displace a country’s existing decision-making structures (which could be independent or influenced by rival powers such as the U.S) and replace them with one’s own. Likewise, it takes a lot more than not delivering new fighter planes in order to defend that influence, assuming one is of the view that Russia already has that level of influence in Damascus, which is not the case.

Russia’s Role in the War

For the entirety of this conflict, Russia had worked to protect the overall integrity of the Bashar regime, particularly the military and its continued ability to fight the rebels. Russia, like its counterparts in the West and in the Middle East, would prefer to not deal with a new Syrian establishment that can be – in disposition and perhaps one day in action – hostile to it. This is explored in additional detail in a later section of this article, but in general, Russia is on the same page as the U.S when it comes to rebel groups that refuse to join the table and work with the existing regime (and its time-honoured commitments to these powers and their respective interests in the country and region).

An area I feel where the Russians have been the most impactful in their support of Bashar is the Syrian Arab Air Force (SyAAF). The SyAAF has and continues to be a critical mechanism for Bashar in his fight against the opposition.

The entirety of the SyAAF’s fighter combat fleet is composed of Russian aircraft such as the MiG-29, MiG-25, MiG-23, Su-24, Su-22 and MiG-21. That said, a number of Czech-built L-39 trainers were equipped for ground attack as well (Bellingcat). According to an analyst on Bellingcat (whose article I strongly recommend reading), the SyAAF fleet continued to see routine upgrades and maintenance support from the Russians throughout the civil war.

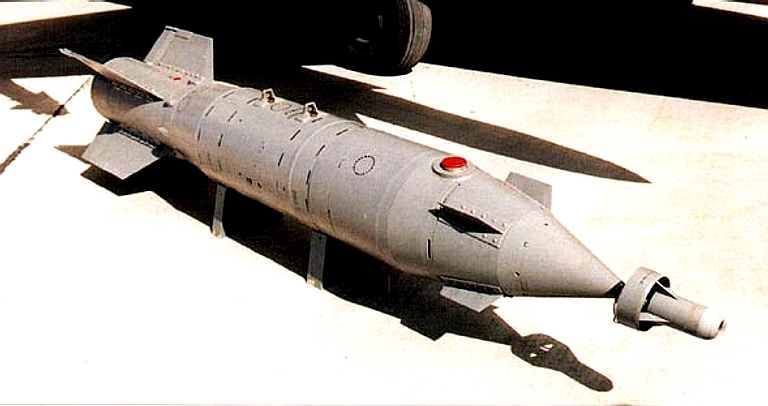

For example, 21 SyAAF Su-24MKs were upgraded in Russia from 2010 to 2013, enabling the SyAAF to engage in precision laser-guided strikes using the KAB-500 and KAB-1500 laser-guided bombs (LGB – for an understanding of what LGBs are, refer to this piece). According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), the SyAAF received 100 KAB-500/1500 units from Russia in 2012-2013.

Although not listed by SIPRI, ‘Oryx’ (the analyst on the Bellingcat piece referred to above) noted that Syria had begun receiving shipments of S-8 80mm rockets in October 2013, enabling SyAAF fighter-bombers and helicopters to engage in strikes against relatively better protected shelters. Thus, it is possible that the SyAAF may have taken delivery of (or will in the near future) of other munitions, such as air-to-surface missiles, which could enable it to engage in air strikes at long-range, giving the rebels less time to prepare or avoid getting hit by air strikes.

While it is clear that Russia’s support to the SyAAF is in clear support of Bashar’s regime, the less intuitive but equally important aspect is the ‘support’ the U.S itself is offering. Despite leading an armed coalition in the region, the U.S has not engaged in any overt air strikes against any of Bashar’s forces, but has instead focused its efforts on deprecating groups such as Jabhat an-Nusra and ISIS. In contrast to what had occurred in Iraq, where Saddam and his establishment were thoroughly rooted out, the U.S is clearly willing to see Bashar’s apparatus pull through to the end of this war.

The Russian Military Buildup in Syria

It is important that we have a more thorough look at exactly what is part of the recent Russian military buildup in Syria in order to understand Moscow’s possible aims. In terms of aircraft, the balance of their expeditionary fleet is composed of primarily strike-oriented platforms, e.g. the Su-24 and Su-25.

The Su-24 ‘Fencer’ is a fighter-bomber “designed to penetrate hostile territory and destroy ground and surface targets [under all] weather conditions, day and night” (AirForce-Technology). In addition to KAB-500/1500 LGBs, the Su-24 can also make use of air-to-surface missiles such as the Kh-29LT and Kh-59.

The Su-25 ‘Frogfoot’ is a low-speed ground attack and close air support (CAS) aircraft. In many ways it is similar to the American A-10 Warthog, and like it, it is designed to provide sustained air cover to ground forces. It can be equipped with laser-guided air-to-surface munitions such as bombs and missiles.

The Su-30M ‘Flanker’ is a multi-role fighter capable of effectively engaging in air-to-air and air-to-surface missions. The Russians can readily use these fighters to engage in long-range strikes, making use of the fighter’s considerable ferry range and high payload.

Clearly, the Russians have come prepared for a fight against the various rebel factions, but the question is, how will their strike capabilities be put to use? Will the Russians go after the opposition? One has to ask, are 28 combat aircraft enough to engage in the number of sorties necessary to completely deprecate the opposition? Did the Russians deploy enough personnel on the ground to defend against the response? I do not think so. The capacity of the Russian force is enough to seriously dent – if not scuttle – any attempt at rebel mobilization against certain targets (like the airport in Latakia), and thus, potentially enough to keep the Bashar-regime standing to the end, but it is not enough to destroy the Syrian Opposition or ISIS.

If we refer back to Kerry’s statement above, “It is the judgment of our military and most experts that the level and type represents basically force protection, a level of protection for their deployment to an air base given the fact that it is in an area of conflict.” (Financial Times), it is clear that the Russian military buildup in Syria is there to defend what Bashar has left (e.g. Latakia) from further erosion, not to completely reverse the current outcome of the conflict. Of course, one could speculate that this is merely the initial cadre of a wider Russian engagement, but we will have to wait and see if that is the case.

What are Russia’s Aims?

It should be noted that Russia, like its Western and even regional Middle Eastern counterparts, is not in the mood of seeing Islamic groups such as Jabhat an-Nusra and others command Syria. America has been looking to find or create suitable actors to succeed Bashar and help it (Washington) maintain its interests in the region (and more importantly, not actively work against them). But that clearly is not and has not been working out, as seen with the recent reports of a U.S-trained rebel commander surrendering arms and vehicles to Jabhat an-Nusra (The Guardian).

While the Syrian population is not going to tolerate Bashar, the U.S and Russia have little choice but to keep Bashar around until a suitable alternative emerges. Vitaly Churkin, Russia’s ambassador to the U.N, said, “I think this is one thing we share now with the United States, with the U.S. government: They don’t want the Assad government to fall. They don’t want it to fall. They want to fight (ISIS) in a way which is not going to harm the Syrian government” (CBS News). That said, the U.S is still keeping an eye out for a post-Bashar figure, as indicative in U.S Secretary of Defense Ash Carter’s statement, “To pursue the defeat of ISIL without, at the same time, pursuing a political transition, is to fuel the very kind of extremism that underlies ISIL” (Defense News).

What Russia can achieve with its military buildup in Syria is preventing the complete erosion of Bashar’s establishment, i.e. not simply his government, but the wider Syrian state apparatus, e.g. its military. The Syrian opposition groups that are still focused on getting rid of that apparatus are now stuck between three walls that are attempting to close in on them: ISIS, which has – for the most part – focused its efforts on cannibalizing the gains of other rebel groups (Carter Center); the U.S, who is looking to find an amicable alternative to the current crop of rebels to take over from Bashar and steer the country out of the war; and Russia, who is working to keep the key vestiges of Bashar’s regime alive through to the end of this conflict.

Should the international community succeed in steering the civil war in Syria to its desired direction, Russia – with its on the ground presence – will almost certainly be involved in any post-war discussion.