The Pakistan Air Force’s (PAF) development efforts for this decade are driven by three factors: First, Pakistan’s skirmish with India in 2019. Second, the ongoing Russia-Ukraine War. Third, the increasing availability of advanced military technology from key partners like China and Turkiye.

Of these, the initial catalyst the skirmish with India, which led to Operation Swift Retort, the PAF’s air operation over India in retaliation to the latter’s incursion in Balakot, Pakistan.

The Balakot episode exposed both tactical gaps for the PAF and, for the Pakistani military generally, a strategic concern. The tactical gap was the freedom India had in undertaking stand-off range strikes from its side of the border. While such an attack was an eventuality (since the PAF also had comparable munitions), the fact that it occurred in peacetime was a problem.

Up until 2019, Pakistan had relied on the idea that its nuclear weapons capability would deter enemy attacks, be it nuclear or conventional.[1] The basic rationale was that any adventure would result in escalation which, eventually, will lead to a nuclear exchange and, therefore, mutually assured destruction (MAD). Nuclear weapons were supposed to prevent military incursions by India.

Not only has India disregarded the nuclear umbrella, but it also created another problem: the risk of additional ‘probing.’ From Pakistan’s standpoint, if the PAF did not respond to the Balakot attack with Operation Swift Retort, it would be at risk of India carrying out additional strikes. These strikes could extend deeper into Pakistani territory and, in turn, create widespread insecurity and instability across Pakistan’s frontiers, especially Azad Kashmir and Northern Areas.

Nuclear weapons will not deter this activity; thus, Pakistan had to start investing in its conventional capabilities from land, sea, and air. Basically, it began taking conventional deterrence seriously, even amid economic uncertainty and fiscal vulnerability.

For the PAF, this conventional deterrence posture would require building upon the template of Swift Retort, arguably its largest air operation to date. Swift Retort involved a composite mix of 12 to 18 fighter aircraft, an airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) aircraft, and an electronic attack (EA) and electronic countermeasures (ECM) aircraft.[2] To the PAF, Swift Retort was a success in that it not only demonstrated a retaliatory capability, but it also inflicted greater damage unto India than what the IAF achieved through Balakot, at least in technical terms. For example, the IAF lost a MiG-21bis alongside a Mi-17 and, according to the PAF’s claims, a Su-30MKI.[3]

If Swift Retort was a template for success, then the PAF needs to demonstrate that it can undertake Swift Retort-type operations at scale, either in quick succession or, possibly, simultaneously. If India concluded that incursions in Pakistan would lead to equally, if not more, costly reprisals, it may walk away from such adventures. Thus, the PAF’s offensive capability must greatly improve.

However, strong retaliatory capability only forms one half of the conventional deterrence equation. The PAF also worked to improve its area-denial capabilities such that it can neutralize an incursion, which would not only mitigate damage in Pakistan but, in turn, lessen the pressure on the PAF to carry out a retaliatory strike. Moreover, an increased risk of failing to carry out a successful strike may also deter India from engaging in an adventure in the first place.

Thus, the PAF’s air warfare plans for the rest of the 2020s aim to achieve two overarching goals: area-denial and the ability to sustain large-scale air operations. The PAF is working to fulfil these goals via seven core areas of work, namely:

- Replacing Legacy Platforms

- Taking a Holistic Approach to Area Denial

- Enhancing Tactical and Strategic Situational Awareness

- Incorporating Drones into the Air Attack Element

- Expanding Air Lift and Logistics Capabilities

- Revising the Advanced Air Training Regimen

- Building Dedicated Offensive Wings

Timely Defence News with Verified Insights

Get the latest Pakistani defence news with reliable research and accurate forecasting

Click Here

1. Replacing Legacy Platforms

In a public relations video released in January 2024, the PAF said that Air Headquarters (AHQ) made the “strategic decision to phase out legacy systems” while showing footage of the Dassault Mirage III and 5, Chengdu FT-7P, Karakoram Eagle (KE) airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) aircraft, and CN-235 light transport aircraft.[4] Overall, the PAF is working to phase out older aircraft and, at least among its special mission aircraft, consolidate its fleets.

Fighter Aircraft

The PAF’s push to replace the F-7P, FT-7P, and F-7PG as well as Mirage III/5 is not surprising. In 2016, the PAF stated that it aimed to replace 190 legacy fighters by 2020.[5] Then Chief of Air Staff (CAS), Air Chief Marshal (ACM) Sohail Aman added that the PAF sought to maintain a 400-strong fighter fleet so that it could hold a 1:1.35 to 1:1.75 ratio against the Indian Air Force (IAF).[6]

The promotional video suggests that the PAF is now pressing ahead with replacing its legacy fighters. While it did not disclose a revised timeline, it appears that the complete shift away from the F-7 and Mirage III/5-series could take place in the short-term, i.e., the next three to five years, or 2030 at the latest. The new fighters will comprise of the J-10CE and the JF-17C (Block-III) in an interoperable high-low mix. Currently, the PAF has 20 J-10CE and 30 JF-17Cs, but Quwa expects that the PAF will acquire additional airframes across both fighter types through the 2020s.

But in November 2023, reports emerged of the PAF speaking to the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC) for an unspecified number of Hongdu L-15Bs for a lead-in-fighter-trainer (LIFT) need. In fact, the PAF sought a new LIFT since at least 2017 to better prepare its pilots for 4/4+ generation jets like the J-10CE, JF-17, and F-16. The PAF had originally planned to use the JF-17B for this role in 2015, but in 2017, it pivoted to seeking a separate platform. Interestingly, the PAF laid out that its new LIFT should have an afterburning engine, multimode radar, and tactical datalink (TDL).[7]

The PAF’s LIFT requirements point to a fully functional fighter, and on that front, the L-15B delivers. It has a passive electronically scanned array (PESA) radar paired with SD-10 beyond-visual-range (BVR) air-to-air missiles (AAM), capacity to deploy precision-guided bombs (PGB) and laser-guided bombs (LGB), and compatibility with targeting pods and electronic countermeasures (ECM) pods.

With these features, the L-15B matches the operating environment of the PAF’s frontline fighters. However, the PAF could also leverage these capabilities for certain missions, especially internal security efforts, like counterinsurgency (COIN) or point air defence.

Thus, the L-15B could emerge as a replacement for some of the PAF’s legacy fighters, such as the F-7PG. However, its value would go beyond taking on the F-7PG’s air defence role. By owning the PAF’s COIN requirements, the L-15B can free the PAF to fully commit its more sophisticated fighters against its external threats. This approach could free up aircraft to allocate to the PAF’s offensive wings on a full-time basis.

Currently, the PAF has 20 J-10CE, 75-odd F-16A/B Block-15 and F-16C/D Block-52, 30 JF-17C, 26 dual-seat JF-17B, 62 JF-17 Block-II, and 50-odd JF-17 Block-I. In total, this would amount to 263 out of 400 4/4+ generation fighters, leaving a requirement of around 140 additional aircraft…

Special Mission Aircraft

The apparent plan to retire the KE AEW&C was unexpected. Inducted in 2009, the KE pairs the ZDK03 PESA radar to the Shaanxi Y-8F600 turboprop-powered transport aircraft. The KE has been a key part of the PAF’s maritime operations, where the PAF deployed the AEW&C in joint maneuvers with the Pakistan Navy (PN). It appeared that the KE was interoperable with the PN’s assets.

Moving forward, it seems that the PAF is standardizing on the Saab 2000-based Erieye AEW&C. The PAF had originally planned to only operate the Erieye in the early 2000s. However, in the late 2000s, it complemented its fleet of four aircraft with four KEs from China. In 2012, the PAF had lost three of its four Erieye AEW&C to a terrorist attack on Minhas Air Base. Ironically, the four KEs were a critical asset for the PAF as it filled the coverage gap caused by the loss of Erieye AEW&Cs.

By 2016, the PAF restored its Erieye fleet to its original strength of four aircraft and, in 2017, ordered another three aircraft. This was followed by an order for at least two additional systems in 2020, the deliveries of which took place from 2020 to 2023. Thus, the PAF has a total of nine Erieye AEW&Cs.

To support this enlarged fleet, the PAF may have decided to reassign personnel from the KE to new Erieye aircraft. In turn, the PAF will likely station several Erieye AEW&Cs in Southern Air Command; it would take up the KE’s role of supporting maritime operations in coordination with the PN.

It is also worth noting that the PN is also building its own AEW capability through its next-generation long-range maritime patrol (LRMPA) aircraft, the Sea Sultan. The PN may add the AEW capability via the Sea Sultan’s primary search radar. If the PN opts for the Leonardo Seaspray 7500 V2 (a variant of the radar used onboard the PN’s RAS-72 Sea Eagle MPAs), it would gain an AESA radar with both air-to-air and air-to-surface tracking and imaging modes. Though not as robust as a dedicated AEW&C, the PN can combine the AEW element of its LRMPAs with the Erieye’s coverage via a TDL.

Standardizing on the Erieye also confirms a key factor – the Erieye can indeed support Link-17, the PAF’s in-house TDL alongside Link-16 and NIXS, the PN’s TDL. The PAF could leverage off-the-shelf solutions, like the MilSOFT Multi-Data Link Processor (Mil-DLP), to enable the Erieye to support and manage multiple TDLs simultaneously. Thus, there is no technical limitation stopping the PAF from connecting the Erieye to the F-16s, JF-17s, J-10CEs, or any other platform.

Logistics Aircraft

It also appears that the PAF is phasing out its four CN-235 light transport aircraft. Since acquiring the original batch in 2005, the PAF did not grow the CN-235 fleet with additional units.

It is unclear if the PAF lost interest in building a lightweight/tactical airlift capability or, instead, has conferred the role to even lighter aircraft, like the Piper M-600 or Beechcraft Super King Air. It is also possible that the PAF did not utilize the CN-235 in its intended role as much as it originally intended to; thus, it opted to replace the CN-235 with aircraft more suited for its actual needs.

The retirement of the CN-235 opens the question of how the PAF plans to drive missions for special operations forces (SOF). The PAF may have opted to grow the Hercules fleet via ex-Belgian C-130H aircraft to assume that role as well as grow its wider air logistics/transport capability.

2. Taking a Holistic Approach to Area Denial

In 2019, the PAF had largely leaned on its fighter fleet to deny enemy aircraft access and control of its airspace. Surface-to-air missiles (SAM) did not figure much in the PAF’s approach, especially as its longest-range ‘vector’ at the time was the MBDA Spada 2000-Plus, which had a range of 20 km.

PAF mostly used its SAMs to protect installations, not deny – much less deter – enemy air activity near or across the national border. While it continued investing heavily in fighters since 2019, the PAF also revealed that it built a new and robust ground-based air defence system (GBADS). AHQ likely appreciated Ukraine’s deft use of GBADS as a way of mitigating enemy air power over one’s territory and, in turn, adopted the idea to defend Pakistani airspace.

However, it is worth noting that in addition to medium- and long-range SAMs, the PAF also set the groundwork for leveraging directed energy weapons and passive air defence measures. This was likely done to address the threat of loitering munitions and swarming drones.

Multirole Combat Aircraft

Moving forward, the PAF’s combat aircraft inductions will solely comprise of solutions with AESA radars, integrated ECM, helmet-mounted display and sight (HMD/S), and compatibility with long-range air-to-air missiles (LRAAM) and high off-boresight (HOBS) AAMs.

The PAF’s procurement roadmap for the rest of this decade – and possibly well into the 2030s – will center on the J-10CE and JF-17C/Block-III in a hi-and-lo mix, respectively. Both fighter types will be used for air-to-air and air-to-surface engagements, with the JF-17C managing the bulk of stand-off weapon (SOW) deployment in the near-term. Combined, the two fighters will play the leading roles in supplanting the remainder of the PAF’s old F-7P/PG and Mirage III/5s.

J-10CE Dragon

The PAF inducted the Chengdu J-10CE in March 2022 as part of a longstanding effort to acquire an off-the-shelf fighter to augment its F-16 and JF-17 fleets. Quwa was able to visually verify a total of 20 J-10CEs in PAF service, substantiating an apparent leak of the contract signed with AVIC, which also listed the sale of 240 PL-15E LRAAMs.

While Swift Retort catalyzed AHQ to sign the deal, the PAF sought an off-the-shelf fighter since at least 2015. It originally wanted to acquire additional new-built F-16C/Ds (for which it once aimed to build a fleet of at least 55 aircraft before the 2005 earthquake in Kashmir). Unfortunately, a chill in defence ties with Washington derailed those efforts, pushing AHQ to look to Russia and China.

Realistically, the only viable alternative to the F-16s was the J-10CE. Not only did the PAF maintain close ties with China, but the J-10CE could also readily leverage many of the PAF’s existing air-to-air munitions stocks (like the SD-10 and PL-5E). The J-10CE was already interoperable with the JF-17. Moreover, AVIC also worked to deliver the first batch of fighters within only eight months after signing the contract, a major feat seeing how net-new inductions can take 18 to 24 months…

End of excerpt. Subscribe to Quwa Premium to read the rest of this section.

JF-17B/C Thunder

While the J-10CE dominates the conversation, the PAF is still invested in the JF-17, especially the latest models, the dual-seat JF-17B and the JF-17C or Block-III.

While the PAF’s baseline fighter, the JF-17C uses an AESA radar with HMD/S and ECM. The KLJ-7A radar has a range of 170 km against targets with a radar cross-section (RCS) of 5m2. It can track 15 targets simultaneously as well as engage four at once. It uses a Chinese HMD/S (likely the same model used onboard the PAF’s J-10CE) paired with a HOBS AAM. It can also leverage the PL-15E.

The JF-17B/C lacks the aerodynamic performance or reach of the J-10CE, but the Thunder is still a viable defensive fighter, one the PAF can afford to acquire at scale thanks to its existing operating infrastructure, local production capacity, and lower costs.

The PAF had originally planned to acquire 50 JF-17Cs; thus far, it only committed to 30 units.[9] The PAF likely split its JF-17C order with the dual-seat JF-17B. It is worth noting that the JF-17B is still largely similar to the JF-17C – i.e., it uses the new fly-by-wire (FBW) flight control system, has the capacity to support an AESA radar, and other improvements.[10] Thus, the PAF can bring its JF-17Bs towards a common configuration with the JF-17C, giving it 56 ‘advanced model’ JF-17s in total…

End of excerpt. Subscribe to Quwa Premium to read the rest of this section.

L-15B

Compared to the J-10CE and JF-17B/C, the L-15B is less certain as the PAF has yet to officially confirm if it is actively pursuing the platform. That said, the L-15B can operate as a functional fighter aircraft, one that could deploy the SD-10 LRAAM. This could be valuable as an internal security or point air defence asset behind the J-10CE, JF-17C, F-16, and JF-17 Block-I/II.

Timely Defence News with Verified Insights

Get the latest Pakistani defence news backed by verified sources and insightful analysis.

Click Here

Surface-to-Air Missiles

The PAF is no longer relying on only fighter aircraft for area denial; rather, SAMs will help improve its first-response mechanism against enemy air activity. To this end, the PAF has begun investing in both medium-to-long-range SAMs and long-range SAMs.

Until recent years, the PAF’s primary SAM solutions were the MBDA Spada 2000-Plus, French Crotale 2000, and Mistral man-portable air defence systems (MANPADS). Traditionally, the PAF’s GBADS was not built for territorial defence, but point-defence over installations, like air bases and radar sites.

Now, however, the PAF considers its GBADS a crucial asset for territorial defence, one meant to work in close concert with its fighter fleet. The new PAF GBADS is a multi-layered system made up of long-range, medium-range, and short-range SAMs plus other active and passive anti-air systems, such as directed energy weapons (DEW) and electronic attack (EA) systems.

HQ-9BE

In its promotional video, the PAF confirmed that it inducted the HQ-9BE, a long-range SAM system. It can intercept a variety of target types, including:

- Combat aircraft at a range of up to 260 km and altitude of 27 km

- Air-to-ground missiles (AGM) at a range of up to 50 km and altitude of 18 km

- Cruise missiles at a range of up to 25 km and altitude greater than 0.02 km

- Tactical ballistic missiles (TBM) at a range of up to 25 km and altitude of 18 km

The HQ-9BE missile’s guidance suite uses an inertial navigation system (INS) aided by a land-based targeting radar via datalink and a terminal-stage active radar-homing (ARH) seeker.

Unlike the older HT-XXX series of guidance radars found on the FD-2000, the HQ-9BE uses the JSG-400 TDR guidance radar, which is designed for TBM interceptions, and the JPG-600 TDR surveillance radar. Furthermore, the battery utilizes a command-and-control (C2) system and electronic counter-countermeasures (ECCM) system, plus several decoy vehicles.

The HQ-9BE is marketed as a limited theater air defence solution that could intercept fighter aircraft and long-range munitions. China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC) says that the HQ-9BE can intercept TBMs with ranges of up to 1,000 km. The HQ-9BE can respond against TBMs in 10 seconds and non-TBMs within 15 seconds. It is basically the PAF’s most advanced SAM system.

The PAF specifically highlighted counter-TBM and counter-cruise missile capabilities. While this was likely in reference to the HQ-9BE, it may indicate that the PAF is interested in the idea of building anti-ballistic missile (ABM) capabilities in the long-term. The HQ-9BE could be the starting point.

End of excerpt. Subscribe to Quwa Premium to read the rest of this section.

Electronic Warfare

For the PAF, electronic warfare (EW) was traditionally an essential part of its offensive operations; but it is now leveraging EW for area denial. In its promotional video, the PAF highlighted at least three new land-based EW systems: HISAR-1, MIGAES, and EADS…

End of excerpt. Subscribe to Quwa Premium to read the rest of this section.

3. Enhancing Situational Awareness

The PAF is using a range of radars and passive sensors to build its situational awareness, not just over Pakistani territory, but, potentially, across its borders too.

Multi-Layered Radar Coverage

The PAF’s radar coverages use a combination of land-based radars and airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) systems. Together, these assets monitor Paksitani airspace across multiple radar bands while also providing support for different missions, including offensive operations.

Horizon-7

It appears that the PAF has begun designating its Erieye AEW&C as the ‘Horizon-7’. The PAF operates seven to nine Erieye systems, with the latest unit being inducted as recently as January 2024.

With the Saab 2000 as its aircraft platform, the Erieye is an S-band active electronically scanned array (AESA) radar with a range of 450 km. It also has five onboard mission operator consoles for managing connected air and surface assets for air-to-air and air-to-surface maneuvers.

Being an airborne radar system, the Erieye also gives the PAF with over-the-horizon (OTH) coverage, which it can leverage to monitor the airspace of its neighbours, especially India and Iran.

It appears that the PAF is standardizing its AEW&C fleet on the Erieye. Moreover, its latest unit – i.e., 23-058 – exhibited some different hardware compared to the PAF’s preceding Erieye units. This unit is unlikely to be the Erieye-ER, but it may have updates similar to Brazil’s E-99M, which is an upgraded Erieye system. That said, the PAF may seek the Erieye-ER in the future, but as an offensively oriented asset that can support its long-range strike wings.

YLC-8E

The PAF also confirmed that it has inducted the YLC-8E radar from the China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (CETC). The YLC-8E is marketed as an ‘anti-stealth radar system,’ but to the PAF, it likely serves as a land-based early warning radar system…

End of excerpt. Subscribe to Quwa Premium to read the rest of this section.

TPS-77 MRR

The PAF also confirmed that it inducted the Lockheed Martin TPS-77 Multi-Role Radar (MRR). While it did not disclose how many units it acquired, some observers peg the number at over 20 radars. The PAF acquired the TPS-77 MRR for its low-level gap-filler radar requirement…

End of excerpt. Subscribe to Quwa Premium to read the rest of this section.

Passive Sensors

The PAF confirmed that it inducted at least one passive sensor, among them the ERA VERA-E and a Chinese system (that may or may not accompany the CHL-906, as explained above)…

4. Incorporating Drones into Air Attack Element

Drones are not new to the PAF. For example, the Leonardo Falco has been a fixture of the PAF’s ISTAR capability since at least the late 2000s. From the early 2010s, however, the PAF started using armed unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) in the ground attack role via the NESCOM Burraq.

In the subsequent years, the PAF has steadily increased its investment in drones, including medium-altitude long-endurance (MALE) and high-altitude long-endurance (HALE) UAVs. By acquiring a wide range of drones, the PAF may be planning to use UAVs in a variety of missions/roles.

MALE and HALE UAVs

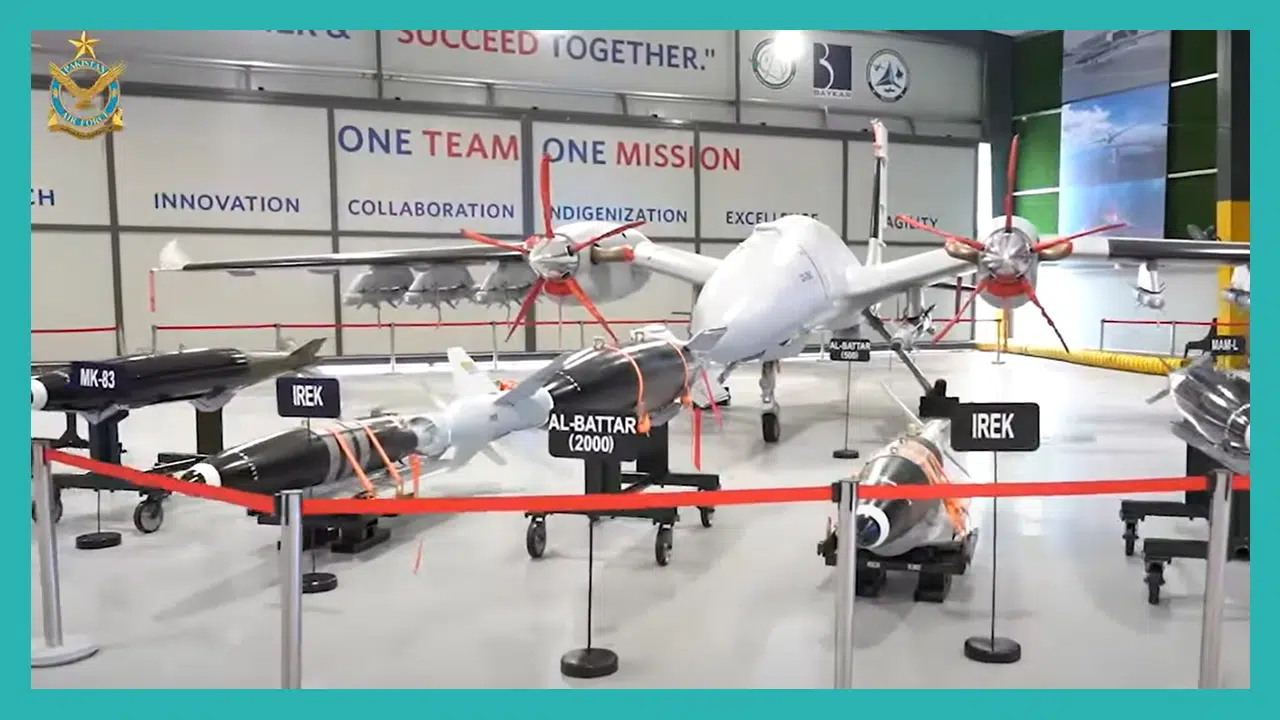

The PAF’s growing drone inventory leverages a mix of foreign and domestic designs across many size and weight classes, from the 700 kg Bayraktar TB2 to the 6,000 kg Bayraktar Akıncı.

Bayraktar Akıncı

In 2023, the PAF revealed that it inducted the Bayraktar Akıncı, a HALE UAV with a maximum take-off weight (MTOW) of 6,000 kg. It is the largest UAV in use by the PAF, offering an endurance of 24 hours and a payload capacity of 1,500 kg across eight hardpoints.

Through its promotional footage, the PAF confirmed that it intends to use the Akıncı in the strike role; for example, it has configured the Akıncı with the IREK, which can reconfigure Mk82 and Mk83 general purpose bombs (PGB) into gliding PGBs.

The Akıncı design is capable of deploying other stand-off range weapons (SOW) as well, such as air-launched cruise missiles (ALCM). The PAF seems to be pursuing this option via a collaborative effort with Baykar Group. For example, the two entities are jointly developing the KaGeM V3, a lighter weight ALCM that may complement the Taimur/Ra’ad-series ALCMs…

End of excerpt. Subscribe to Quwa Premium to read the rest of this section.

Loitering Munitions

The PAF also revealed that it has inducted a loitering munition, i.e., the ‘YX’ jointly produced by the National Aerospace Science and Technology Park (NASTP) and Baykar Group. Though inducted, this ‘YX’ appears to be an iterative program as there is a newer version – or evolution – in developed called the ‘Python.’ In either case, this design seems to be stand-alone in that it does not depend on a launch platform; rather, it launches independently…

End of excerpt. Subscribe to Quwa Premium to read the rest of this section.

5. Expanding Air Lift and Logistics Capabilities

Though it is apparently retiring its four CN-235s, the PAF is expanding its airlift capabilities as a whole, with a stronger focus on growing its Hercules fleet. To that end, the PAF ordered seven second-hand C-130H aircraft from Belgium. Four of these aircraft have been inducted as of 2023; it is unclear what will happen with the remaining three units.

C-130H

The ex-Belgian C-130Hs will join the PAF’s 5 C-130B and 9 to 11 C-130E. The PAF upgraded its C-130B and C-130E between 2014 and 2017. It will be worth seeing if the PAF configures its C-130H’s avionics suite along similar lines of its C-130B/Es, which use the Rockwell Collins Flight2…

End of excerpt. Subscribe to Quwa Premium to read the rest of this section.

6. Revising Advanced Air Training Program

The PAF’s entire fighter fleet will shift to 4-generation and 4-generation-plus aircraft by the end of this decade, with the bulk of the fleet leveraging AESA radars, HMD/S, and integrated ECM. Thus, the PAF sought a dedicated LIFT to familiarize its new pilots with these technologies before jointing a frontline J-10CE, JF-17, or F-16 squadron. Beyond 2030, these new pilots may join a stealth fighter unit.

In 2015, the PAF stated that it was interested in using the JF-17B as a lead-in-fighter-trainer (LIFT); and it was frank about its disinterest in a smaller aircraft for the role. Its main concern was that the dedicated LIFT like an L-15 would have high operating costs, potentially at-par with the JF-17.

However, in 2017, the PAF pivoted from the JF-17B to exploring dedicated LIFT designs, namely the AVIC L-15B and Leonardo M-346. In 2023, the PAF reportedly began negotiations for the L-15B.

L-15B

When discussing its LIFT requirements, the PAF highlighted three core requirements: afterburning engine, multi-mode radar, and tactical datalink (TDL)…

End of excerpt. Subscribe to Quwa Premium to read the rest of this section.

7. Building Dedicated Offensive Wings

The Balakot episode exposed the need for an improved rapid response, area-denial capability; hence why the PAF acquired the HQ-9BE long-range SAM. These will augment the PAF’s growing force of AESA radar- and LRAAM-equipped fighter aircraft.

However, building a retaliatory capacity was equally important for deterrence purposes. Mitigating a cross-border strike is not enough, but in Pakistan’s view, it must be followed up with a measured, yet impactful and rapidly employed, response. From Rawalpindi’s standpoint, establishing the threat of extensive conventional retaliation by air and from land could deter a future Balakot issue entirely.

To achieve this goal, the PAF likely concluded that it must build the capacity to support multiple Swift Retort-scale operations, be it in quick succession or simultaneously.

Operation Swift Retort leveraged a composite force of multirole fighter aircraft, AEW&C, and EA/ECM jamming aircraft. Through the rest of this decade, the PAF could orient more of its squadrons for the offensive role so that it can support more Swift Retort-type operations. The induction of the HQ-9BE could free up additional units (that might have otherwise been dedicated entirely for an air defence function) to take on more strike/attack duties. Chief among these units would be the JF-17C and J-10CE squadrons; the Bayraktar Akıncı may complement them as a SOW carrier (that would deploy ALCMs and gliding PGBs from a safe distance within Pakistani territory, like the Mirages did).

The near-term composition could involve the J-10CE in the top-cover and the JF-17B, JF-17C/Block-III, and Akıncı in the strike roles, respectively. Potentially, the JF-17 Block-II may be upgraded with an AESA radar, updated avionics suite, HMD/S, and improved ECM capability. However, the Block-II may be employed for the defensive area-denial role (alongside the F-16s and JF-17 Block-Is).

However, this composition would only be effective in this decade. India is also building a robust – if not standard-bearing – area-denial capability through a plethora of advanced SAMs (e.g., Barak-8) as well as cutting-edge 4+ fighters, like the Rafale and Tejas Mk1A. The PAF likely anticipates a markedly tougher threat environment in India in the future, hence why it is now actively bringing NGFAs into the conversation. The Shenyang J-31 is at the center of this push.

Shenyang J-31

The centerpiece of the PAF’s future offensive air element will be the J-31, a twin-engine stealthy next-generation fighter aircraft (NGFA). The PAF has officially committed to acquiring the J-31.

The PAF’s focus is likely on building an optimal mix of range, payload, and low-observability (LO) – or stealthiness on radar and infrared – in one multirole platform. This one fighter could potentially drive the necessary long-range air-to-air and air-to-surface work of the PAF’s offensive wings…

End of excerpt. Subscribe to Quwa Premium to read the rest of this section.

Manned-Unmanned Teaming

A sign of the PAF’s interest in UCAVs was the reference it made to manned-unmanned teaming (MUM-T). The PAF did not reveal how it will build MUM-T capabilities, but one can reasonably see it using the wider industry’s general direction as its reference point…

End of excerpt. Subscribe to Quwa Premium to read the rest of this section.

New Airborne Standoff Jammer(s)

The PAF has also (albeit indirectly) announced that it will be augmenting its EA/ECM fleet with at least one new airborne stand-off jamming aircraft (ASOJ). This new ASOJ will use the Bombardier Global Express 6000 as its platform. It is unclear if the PAF will acquire the Aselsan HAVASOJ suite or develop an original solution of its own. The number of ASOJs acquired will likely correspond to the number of dedicated offensive wings the PAF is able to raise in the 2020s…

End of excerpt. Subscribe to Quwa Premium to read the rest of this section.

8. Potential Goals

Thus far, the PAF’s development efforts for this decade have been comprehensive in scope, fighter aircraft, drones, SAMs, land-based EW/ESM, land-based EA/ECM, airborne and land-based radars, airlift expansion, and a new stand-off jamming aircraft.

However, there are several underdeveloped areas that the PAF may begin focusing, possibly by the end of this decade, with work carrying through into the 2030s.

Attritable Loyal Wingman UCAV

With a stated focus on MUM-T, the PAF will likely procure attack-capable UCAVs (similar to the Bayraktar Kızılelma or TAI ANKA-3) and an attritable decoy UAV based on a target drone.

But there may be room for an additional type, a design that could fill the space between a sub-1-ton decoy and 9-10-ton UCAV. This could be a 2-4-ton loyal wingman UCAV, which would be capable of deploying air-to-air missiles and small air-to-surface munitions. It could accompany the NGFA and help sustain losses by being the primary decoy and attack option in high-risk environments…

End of excerpt. Subscribe to Quwa Premium to read the rest of this section.

End of Excerpt (5,100/10,223 words)

You can read the complete article by logging in (click here) or subscribing to Quwa Premium (click here).

Timely Defence News with Verified Insights

Get the latest Pakistani defence news with reliable research and accurate forecasting

Click Here

[1] Sadia Tasleem. “Pakistan’s Nuclear Use Doctrine.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. 30 June 2016. URL: https://carnegieendowment.org/2016/06/30/pakistan-s-nuclear-use-doctrine-pub-63913

[2] Alan Warnes. “Operation Swift Retort: One Year On.” Air Forces Monthly. April 2020. Page 35. URL: https://airforcesmonthly.keypublishing.com/the-magazine/view-issue/?issueID=8176

[3] Ibid.

[4] “PAF Checkmates Pakistan’s Enemies.” Pakistan Air Force (PAF) Press Release. 16 January 2024. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V_2Osf0r-p4&ab_channel=PakistanAirForce

[5] “Pakistan Air Force Needs to Replace 190 Planes by 2020.” Dawn News. 15 March 2016. URL: https://www.dawn.com/news/1245714/pakistan-air-force-needs-to-replace-190-planes-by-2020

[6] Bilal Khan. “Pakistan’s Next – Near-Term – Steps for Bridging Airpower Gap.” Quwa. 25 March 2018. URL: https://quwa.org/2018/03/25/pakistans-next-near-term-steps-for-bridging-airpower-gap/

[7] Alan Warnes. Interview. Air Chief Marshal Mujahid Anwar Khan, Chief of the Air Staff, Pakistan Air Force. IHS Jane’s Defence Weekly. 22 May 2019.

[8] Paul Lewis. “Improvise and modernise”. Flight International. 24 February 1999. URL: https://web.archive.org/web/20120304081417/http://www.flightglobal.com/news/articles/improvise-and-modernise-48468/ (Last Accessed: 22 March 2018).

[9] Alan Warnes. “Pakistan’s roaring Thunder.” Air Forces Monthly. May 2021.

[10] Alan Warnes. “Two-seat JF-17B progresses.” AirForces Monthly. April 2017