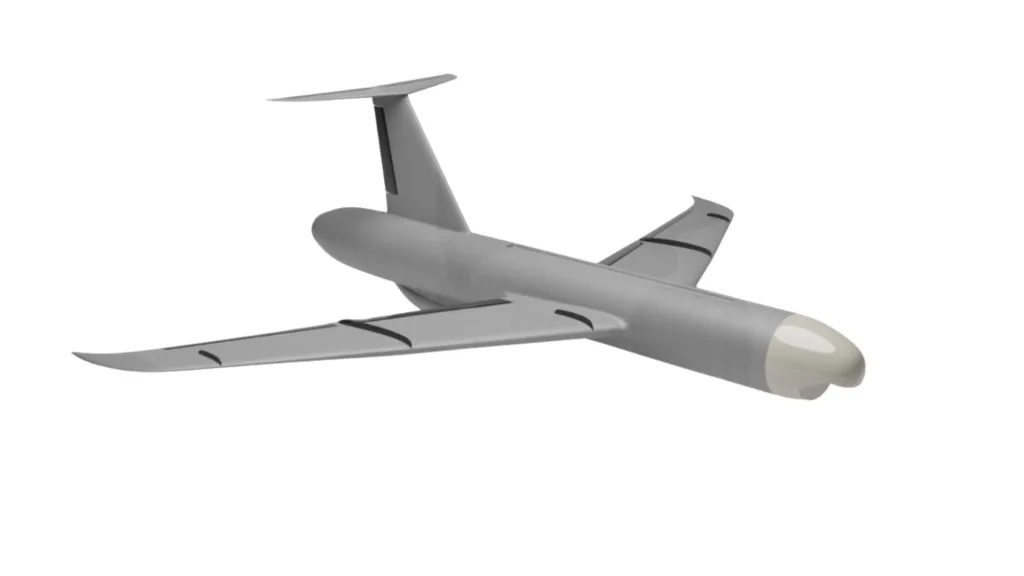

One can define a “One-Way Effector” (OWE) as essentially a jet-powered loitering munition, overlapping with more traditional fan/piston/prop-powered loitering munitions on one end, and the long-range, high-impact cruise missiles on the other. The driving thought of an OWE is to cross-leverage the advantages of scale, range, and speed to saturate enemy air defence systems with the threats that are too fast, too numerous, and, depending on how the OWE is designed, too small to detect early on radar.

An earlier Quwa piece explored the value of an OWE program; in short, countries facing robust, integrated air defence systems (IADS) are investing heavily in this concept. The Russians, in fact, have already developed a system of this type, namely the Geran-3, to help counter and degrade Ukraine’s multi-layered IADS. Granted, these OWEs cost much more than a propeller-driven loitering munition, but the reality is that the underlying approach is in its early stages.

Over time, the defence industry will generally develop suitable inputs (especially engines and aerostructure materials) that can better control costs. OWEs will not be ‘cheap,’ but for their intended purpose, which can potentially include a key suppression or destruction of enemy air defence (SEAD or DEAD) role against far costlier and more strategically vital IADS inputs (such as enemy long-range surface-to-air missile – or SAM – batteries and radars), they could be relatively low-cost solutions.

Operationally, Pakistan could integrate OWEs in multiple domains, such as single-precision strike munitions, a complementary layer in the Army Rocket Force Command (ARFC), a component of SEAD and DEAD led by Pakistan Air Force (PAF) fighter aircraft, munitions for unmanned surface vessels (USVs), and other areas.

Being miniature cruise missiles, OWEs are inherently versatile when equipped with effective guidance systems (e.g., high-fidelity map data and robust protection against communications jammers), ensuring that they successfully strike their targets. OWEs rely on precision as they carry much lighter warheads, lacking the benefit of explosive yield to offset their wider circular error probable (CEP) reach.

OWEs are small-sized subsonic cruise missiles, i.e.. These comparatively high-speed threats are difficult to detect early on radar and, due to their small size and scale (via swarming), relatively challenging to intercept. Besides targeting enemy systems, Pakistan can also use OWEs to force India’s IADS to expend its surface–to-air missile (SAM) and, in turn, create meaningful gaps for large missiles, like the Taimur or Fatah-series, to exploit. Of course, all this would be predicated on scale and whether Pakistan would field enough OWEs to support a genuinely threatening warfighting posture.

The intriguing aspect of Pakistan is that the country is, perhaps more unintentionally than systematically, developing systems that could, in theory, readily become OWEs. However, it doesn’t appear that a cohesive strategy is in place to integrate these systems for the OWE role. This is not necessarily an indictment, as, in fairness to Pakistan, OWEs are relatively new entrants in the munitions space, and currently, most major vendors (including MBDA) have only begun releasing concepts or announcing future products. Likewise, while it deployed the Geran-3 in Ukraine, the results have, thus far, been mixed. Cost is an issue, but Ukraine has also begun adapting to it by using electronic warfare (EW) to degrade the Geran-3’s guidance data links. That said, Russia will adapt to Ukraine’s moves and, potentially, work to make the Geran-3 a more independent and autonomous system.

Overall, both state-owned and private-sector Pakistani vendors have an opportunity to enter the OWE space ahead of adoption and, when the concept gets validated, be ready to absorb potential orders. The challenges, as discussed in the second half of this article, include the usual culprits: a lack of unified adoption planning by the armed forces and questions regarding production scalability.

Get access to this article and all other Quwa content today.

Click Here

Related Reads

- Market Brief: Pakistan’s USV, AUV, and Naval UAV Solutions

- Market Brief: Pakistan’s “Missing Middle” Surface-to-Air Missile Requirement

- Market Brief: Pakistan’s Loitering Munitions Requirement

Through its cruise missile and high-speed target drone programs, the Pakistani defence industry – especially state-owned entities (SOE) like NESCOM – has the capacity to develop OWEs. The aforementioned examples represent the current crop of products that can meet the criteria of OWEs; however, undoubtedly, more designs can be created.

Don't Stop Here. Unlock the Rest of this Analysis Immediately

To read the rest of this deep dive -- including the honest assessments and comparative analyses that Quwa Plus members rely on -- you need access.