In July 2020, the Pakistan Ministry of Defence Production (MoDP) published its “Two Years Performance Report” to outline the activities of the country’s various state-owned defence industry organizations.[1]

One of the MoDP’s notable disclosures in the report was the creation of a draft offset policy document, which, according to the MoDP, “is being circulated to all concerned for input.”[2] The offset document may be an effort to revive or utilize the Directorate General Defence Purchase’s (DGDP) current offset policy.[3]

In addition, the MoDP said it was working on a number of reforms that would encourage greater oversight of its activities, deepen engagement with Pakistan’s private sector businesses and academic institutions, and drive more transfer-of-technology (ToT) arrangements in big-ticket contracts.[4]

The MoDP likely set these goals in response to longer-standing calls for more defence exports and, at least within the Pakistan Navy (PN) and Pakistan Air Force (PAF), support for indigenization efforts. Controlling the cost of defence procurement is a significant contributor to both the offset and indigenization efforts.

However, Pakistan is also at the crossroad of deciding whether it wants to continue investing in its defence industry, at least in regards to specific state-owned organizations.

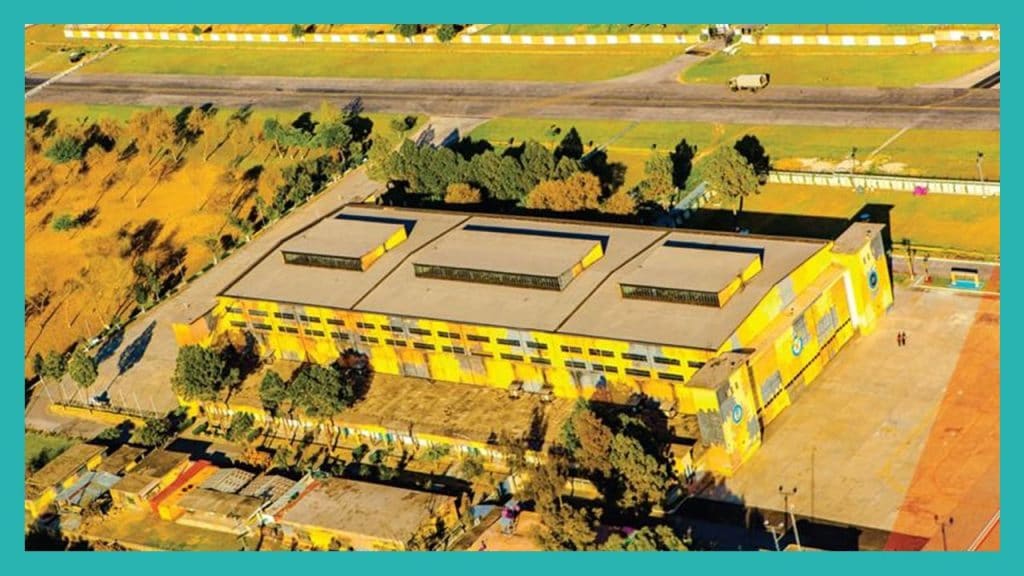

These organizations – such as (among others) Pakistan Ordnance Factories (POF), Heavy Industries Taxila (HIT), Pakistan Aeronautical Complex (PAC), and Karachi Shipyards & Engineering Works KSEW) – form the bulk of the country’s defence industry. In effect, the state is Pakistan’s main domestic defence vendor.

Pakistan formed these organizations to locally support the armed forces’ equipment through overhauling, repair, and other major maintenance tasks. Since 2000, these organizations started manufacturing some major equipment, but with support from original equipment manufacturers (OEM) in China and Europe.

Unfortunately, the armed forces have yet to fully rely on these organizations for these requirements. The Pakistan Army (PA), for example, recently ordered the NORINCO VT4 main battle tank (MBT) from China, even though it already has a domestic MBT program in the form of the al-Khalid series. Given the fact that HIT was not manufacturing at full capacity, the purchase of a solely imported design is curious.

The issue with importing the VT4 (when HIT is not at full capacity) is not solely a question of whether HIT is able to deliver on the PA’s requirements, but if General Headquarters (GHQ) should continue spending money on supporting HIT. Because HIT et. al are state-owned organizations, the overhead cost of running these facilities is borne by the armed forces. In its simplest sense, funding that goes to support an HIT that is not functioning as intended is money going away from new hardware from another source.

Indeed, overhead costs are among the biggest drawbacks of maintaining a publicly run defence industry ecosystem. The armed forces must foot the bill for payroll, infrastructure support, facility upgrades, and a plethora of other commitments such as health care and housing schemes, among others. In crude terms, if an investment of this scale is ‘not working,’ then what is the point of continuing it?

Don't Stop Here. Unlock the Rest of this Analysis Immediately

To read the rest of this deep dive -- including the honest assessments and comparative analyses that Quwa Plus members rely on -- you need access.