2948Views

Analysis: Is Pakistan’s Next Strategic Focus on Boosting Munitions Output?

For countries seeking to maintain a credible measure of conventional deterrence, the Russia-Ukraine War has highlighted the importance of controlling one’s munitions supply line from the design level all the way to production output. As depleting munition stocks became problematic, Ukraine had to wait on approvals to simply secure the necessary technology it needed to resist Russia, e.g., surface-to-air missiles (SAM), or stand-off range weapons (SOW), artillery shells, rockets, and so on.

Perhaps, then, Pakistan’s growing interest in developing its own SAMs and even air-to-air missiles (AAM) reflects this emerging reality, i.e., in war, one cannot take any external supplier for granted. Thus, one must maintain a robust munitions development and production capability to not just keep its war effort going, but potentially, establish some credible level of conventional deterrence. How could one deter an enemy from attacking if the enemy makes depleting their adversary’s limited munitions stocks a strategic goal?

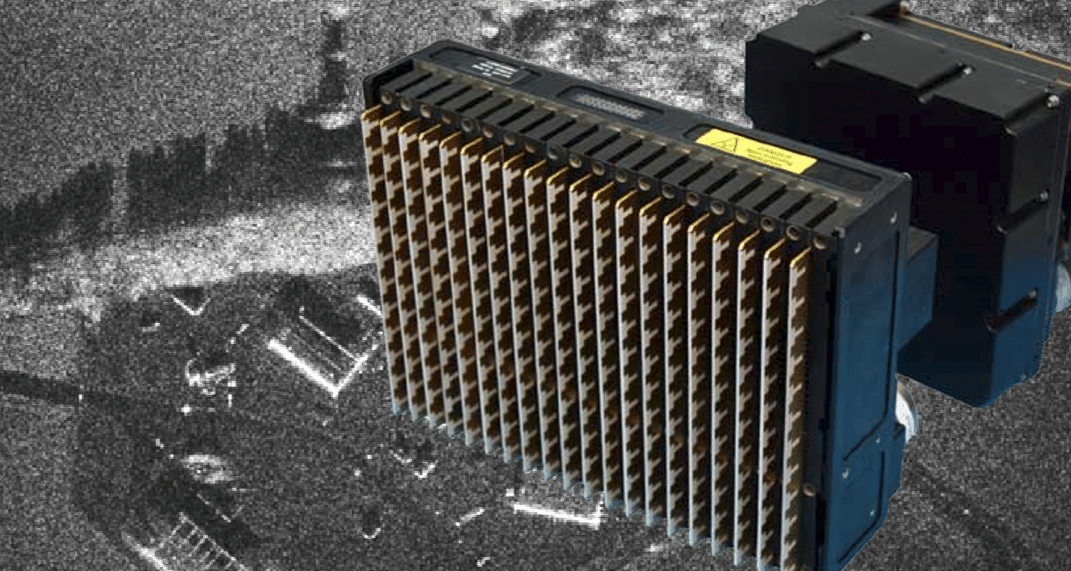

To its credit, Pakistan took some ownership of this issue a long while back, most notably through its heavy investment in mass-producing small arms ammunition, tank and artillery shells, and unguided rockets. But now, the country is expanding its focus towards locally manufacturing guided munitions at scale, both for its domestic needs and, potentially, export. Projects like the Harbah NG anti-ship cruising missile (ASCM), and Taimur air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) headline this effort.

However, offering a portfolio of designs is just one part of the equation. Ukraine’s struggles are exposing the necessity of having a reliable munitions production capability, i.e., churning out guided missiles at scale in both peacetime and wartime. Pakistan’s traditional calculus pegged a conventional war with India lasting several weeks, at which point it would either be resolved at the table or, if needed, escalate into a nuclear exchange (i.e., mutually assured destruction or MAD).

But that calculus was based on Pakistan’s experiences up to that point. The nature of conventional war is also prone to change, especially as new technologies enter the mix and/or doctrines evolve. For example, India formulated a strategy (“Cold Start”) of using rapidly mobilizable land and air assets to quickly enter, capture, and hold Pakistani territory. Pakistan had harped on resorting to nuclear weapons if India breaks a certain threshold, like eroding Pakistan’s conventional capabilities.

With “Cold Start,” India envisaged the idea of using its conventional forces to quickly strike Pakistan and render its nuclear threats moot. But in response, Pakistan formulated the idea of using ‘tactical nuclear weapons’ (TNW). Should India achieve in employing “Cold Start,” Pakistan would use TNWs against those specific Indian formations, thus using the destructive power of nuclear warheads in a more focused way that (theoretically) cannot justify an Indian nuclear response against cities. Put another way, Pakistan said it would use certain nuclear weapons in a ‘non-strategic’ way as though it was a conventional weapon.

Thus, how countries perceive conflict can change based on certain circumstances, such as doctrine, enemy objectives, and technology, to name a few. These changes can alter how Pakistan views conventional war in the future; for example, could ‘enough’ stocks of guided munitions ‘neutralize’ the Indian threat? If one has sufficient stocks of cruise missiles, guided bombs, guided rockets, drones, and other assets, is there a possibility of striking enough military facilities, powerplants, refineries, logistics centres, etc, to end a war?

India will certainly be asking the same question as, long before Pakistan, it sought to design and produce its own lines of SAMs, AAMs, and other guided munitions. In other words, a future conventional war could be less about capturing territory and, instead, racing to cripple the adversary’s warfighting stature. Overall, this picture would necessitate ample preexisting munition stocks, and capacity to rapidly replenish stores.

Thus, scaling up and producing in large numbers is a priority for Pakistan, but as a country with relatively limited industrial capability, this will be a challenging goal…

End of Excerpt (642/1,263 Words)

You can read the complete article by logging in (click here) or subscribing to Quwa Premium (click here).

For more defence industry news and analysis, check out: