2720Views 2Comments

The Rationale Behind Pakistan’s Tactical Nuclear Program

25 October 2015

By Bilal Khan

The recent news about the U.S looking to offer a nuclear technology and fuel deal to Pakistan in exchange for Islamabad curbing its tactical nuclear weapons program was not unexpected. It is no secret that the U.S has not been supportive of Pakistan’s pursuit of nuclear armaments. Following the end of the Soviet Union’s occupation of Afghanistan, the U.S imposed a series of stringent economic and military sanctions on Pakistan in an attempt to dissuade it from continuing with its nuclear weapons program. Instead, Pakistan persisted, and in 1998 it succeeded in carrying out its first uranium and plutonium warhead tests.

After 9/11 the U.S waived its sanctions on Pakistan in exchange for its cooperation in the invasion and occupation of Afghanistan, and while Washington did offer India a nuclear energy deal (giving it access to the Nuclear Suppliers Group or NSG), Pakistan was not directly penalized for its own program, as a matter of fact, it was finally given access to the international arms market, enabling it to freely pursue arms from Western suppliers. Throughout the 2000s and 2010s Pakistan continued advancing its plutonium program (Defense News), eventually succeeding in developing lightweight miniaturized warheads for use on tactical munitions such as cruise missiles and battlefield ballistic missiles (Defense News).

And herein lies a major problem for India. The destructive power of a nuclear warhead is well understood, but the advancements Pakistan has made with its delivery systems are not to be underestimated.

Before going into this topic, it is important to understand the context of the South Asian strategic theatre. To put it briefly, after the nuclear tests, Pakistan relied on nuclear deterrence as a means to dissuade India from opening conventional warfronts on Punjab and Sindh. In response, India decided to work against Pakistan’s ability to use nuclear weapons by formulating “Cold Start”, a doctrine designed to quickly utilize readily mobilized unified battle groups involving infantry, armour and aircraft to move into and hold territory in eastern Pakistan, thus out-timing Pakistan’s nuclear warnings and rendering them moot.

Irrespective of whether Cold Start has been adopted or not, the reality of India’s conventional advantages over Pakistan could not be denied, especially in regards to the maritime and air warfare theatre. So the idea that India could quickly open fronts and swiftly secure territory was a real risk for Pakistan, especially if such movements were to occur and succeed in spite of Pakistan’s nuclear deterrence. Cue Pakistan’s development of miniaturized plutonium warheads, cruise missiles and tactical ballistic missiles.

Even in conventional terms there are numerous advantages to fielding land-attack cruise missiles (LACM). As I discussed in an earlier piece, cruise missiles are difficult to defend against (they are small and capable of flying at very low altitudes, making it difficult for radars to detect them), and they can be deployed on a very wide range of air, sea and land-based platforms. Pakistan has two core LACM channels in use, surface and aerial, with a third – i.e. sub-surface or underwater – likely in development.

The principal platforms are Babur and Ra’ad. The Hatf (Vengeance) VII Babur (named after the first Mughal Emperor) was developed by the National Engineering and Scientific Commission (NESCOM) and is similar in design and concept to the U.S BGM-109 Tomahawk. The cylindrical micro-turbofan (or turbojet – has not been confirmed officially either way) powered LACM has a range of 700km and is capable of flying at sub-sonic speeds. The Babur’s guidance system draws from an Inertial Navigation System (INS), Terrain Contour Matching (TERCOM) and Digital Scene Matching & Area Co-relation (DSMAC) (ISPR). These are network-independent guidance systems as the targeting and navigational information is stored and processed within the missile itself. However, with the introduction of China’s BeiDou Navigational Satellite System (BDS), it is possible that Babur will be aided by satellite-based guidance, allowing it engage in midcourse corrections if necessary.

At present the Pakistan Army is deploying the Babur through land-based vehicles, but it is likely that the Babur will be adapted for use on submarines (such as the Chinese submarines the Navy is in the process of ordering) and possibly even on ships.

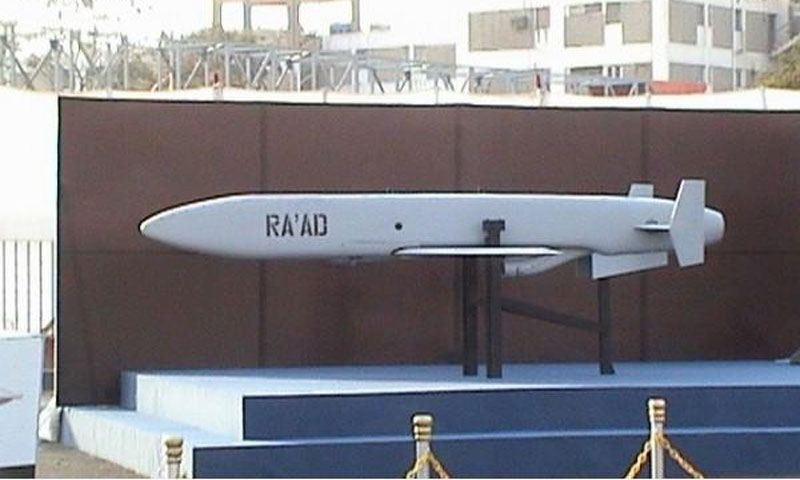

The Ra’ad (“Thunder”) is an Air-Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM) with a range of 350km and is in use by the Pakistan Air Force. It was developed by Air Weapons Complex and NESCOM. Like the Babur the Ra’ad is equipped with a micro-turbojet (or turbofan, unconfirmed) engine, but it exhibits a different airframe design. Like the Babur the Ra’ad is a small flying object, but the Ra’ad builds upon that advantage by having a low-detectability design (it may be benefitting from heavier composite use as well). Otherwise, the core components remain the same, e.g. the use of TERCOM, DSMAC and possibly BDS for guidance.

The Babur and Ra’ad are not static programs. There is nothing to preclude Pakistan from continuing to develop these platforms, especially in terms of range and other major improvements such as ‘stealthier’ (i.e. low-detectability) design and incorporation of sub-munition dispensers.

Jane’s in February 2008 reported that Pakistan signed a series of agreements with Turkey on the development of various technologies, and among them “turbojet motors”, “stealth technology” and “precision-guided bomblets” were on the list.[1] Seeing Turkey’s impressive advances thus far (such as the SOM ALCM and Atmaca Anti-Ship Missile), I am confident Pakistan has both a lot to gain and take seriously with regards to this agreement (and its relationship with Turkey in general).

With the above in mind one can imagine then the threat LACMs present when paired with lightweight low-yield nuclear warheads, especially if Pakistan is able to achieve a high level of ‘distributed lethality’ where it has a large number of able platforms to deliver its LACM from land, sea and air. In such a situation there is nothing India or – to be frank – any other power could do to stop Pakistan from using low-yield nuclear warheads. In addition to its LACM arsenal, Pakistan also developed and put the Nasr battlefield ballistic missile into service: The Hatf-XI Nasr (“Victory”) has a range of 60km and its stated purpose is to serve as a “quick response” system with “shoot-and-scoot attributes” (i.e. the capacity to launch and then quickly move away from the position in order to avoid retaliatory fire) (ISPR).

As Pakistan’s Foreign Secretary Aizaz Chaudhry put it, the country’s nuclear program is “one dimensional: stopping Indian aggression before it happens. It is not for starting a war. It is for deterrence.” The Pakistani nuclear doctrine is not offensive, but rather, it is a means to prevent India from invading, not as an offensive edge for use in pre-emptive strikes (though I imagine some might make that argument, especially in the context of the ‘rogue Jihadi commander’ analogy).

That said, the prospect of a nuclear assault directly unto one’s forward military thrusts is not an easily addressable threat, especially if that nuclear assault is built upon distributed lethality (where one’s own pre-emptive strikes can do little to neutralize the nuclear threat). It would be a very onerous effort for the U.S to deal with this, so imagine India with a thinner quantitative and qualitative edge over Pakistan (not to mention fewer resources than the U.S). And of course some within American circles (i.e. those who really bought into the ‘rogue Jihadi commander’ narrative) see Pakistan’s advancing nuclear warhead and delivery technology as a threat to U.S. interests in the Middle East.

In the midst of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s visit to Washington, the New York Times reported that the U.S government announced that it would sell eight new F-16s to the PAF in an “overture intended to bolster a tenuous partnership.” Granted, there is more to ensuring the longevity of U.S-Pakistani ties than to keep tabs on Islamabad’s nuclear program, but the nuclear dimension cannot be ignored.

While the PAF plays a major role in the military’s campaign against the Taliban in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), particularly during the most and ongoing campaign, Zarb-e-Azb, the PAF clearly would not need additional F-16s for that purpose alone, or at all. The armed forces are well stocked with prime counter-insurgency (COIN) assets in the form of other fighters capable of precision strike (such as the JF-17), armed drones (such as Burraq) and capable (and increasingly expanding) COIN-adept infantry. In fact, if the PAF were truly interested in additional COIN tools, it would request platforms such as the A-29 Super Tucano, which would provide effective close air support (CAS) at a fraction of the cost of F-16s. I am sure the U.S would happily oblige as well considering how such a system would both sharpen Pakistan’s capacity for COIN as well as respect the existing military balance with India.

Thus, the recent F-16 offer is in reality a carrot meant to placate Pakistan’s concerns about the growing conventional gap between itself and India, i.e. the very concern propelling Pakistan’s tactical nuclear program. In a way one could look at it as an indication from the U.S (which has been in place since the start of Pakistan’s nuclear program) that if Pakistan were to curb its nuclear program, it could address its defence needs through conventional arms sales quite easily.

But how can one measure the efficacy of a strong conventional edge against a nuclear one? The latter is strategic and is exponentially more impactful. Yes, strong conventional capabilities would certainly help in an offensive context (as it did in 1965), but (in Pakistan’s eyes) an effective nuclear program makes invading Pakistan a complete non-starter, especially if neutralizing that program militarily is not possible (thanks to distributed lethality). And of course there is the prestige (genuine or perceived) of being in possession of nuclear weapons and the decades long struggles that have gone into them.

[1] Lale Sariibrahimoglu. “Pakistan agrees to further defence co-operation with Turkey.” Jane’s Defence Weekly. February 2008.

2 Comments

by jigsaww

Good one…its laughable how Nasr has become a Dhoti shiverer for our indian neighbours…It is the single most discussed missile in indian media now and i’m sure in indian military headquarters too. Seems like it has decimated the indian cold start even before it became adoptable…though india would not officially accept a cold start like doctrine…to keep element of surprise. We know why C-17s and C-130s with Chinooks are being acquired…but that is why Pakistan will keep its “full spectrum deterrence” …

by MT

Raad is build by denel south africa while babur is complete Chinese CM which chinese developed by rev engineering kh55.

If pak had tech to make CM then it could have easily turned babur into babur ALCM