214Views 0Comments

Pakistan Intends to Rely More on China for Armaments Quwa Premium

In early April 2022, the Pakistan Army’s (PA) Chief of Army Staff (COAS), General Qamar Javed Bajwa, said that Western supply restrictions have pushed Pakistan to lean on China for new defence hardware. Gen. Bajwa issued the statement at the 2022 Islamabad Security Dialogue.

Specifically, Gen. Bajwa spoke to how Pakistan’s defence imports from the West fell through. For example, in 2018, Pakistan had signed a $1.5 billion US contract with Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI) for 30 T129 ATAK attack helicopters. However, TAI was unable to secure an export permit from the United States for the T129’s LHTEC CTS800 turboshaft engines. Likewise, the Pakistan Navy (PN) had sought German diesel engines for the Hangor (II)-class submarines it is buying from China. However, Berlin ultimately refused to release the export permits to transfer the engines for those submarines.

The reasons for the supply-side failures vary. In the case of the T129 engines, the primary issue seemed to have been the chill in bilateral ties between the U.S. and Pakistan. However, with the German engines for the Hangor (II)-class submarines, it is unclear why Berlin withheld the permits. It might have been due to Indian pressure or, potentially, Germany being wary about transferring a key subsystem for a Chinese weapon system. Gen. Bajwa also highlighted that the pressure to win Indian defence contracts also led to France to stop supporting the PN’s Agosta 90B air-independent propulsion (AIP)-equipped submarines.

Ultimately, regardless of the causes driving Western suppliers to shut their shops to Pakistan, the Pakistani military is losing options. As a result, as Gen. Bajwa noted, Pakistan is moving closer to China, particularly in the realm of sourcing high-tech weapon systems.

While Gen. Bajwa’s statements about the difficulty of sourcing weapons from the West are true, one must not discount China’s technology base. Today, China is an economic superpower capable of sourcing every critical input for its marque weapon systems, including multirole fighter aircraft, surface warships, drones, and even submarines. Moreover, Chinese products leverage contemporary technologies. As an example, the J-10CE is equipped with an active electronically scanned array (AESA) radar and long-range air-to-air missile (LRAAM) capable of reaching at least 145 km (i.e., PL-15E).

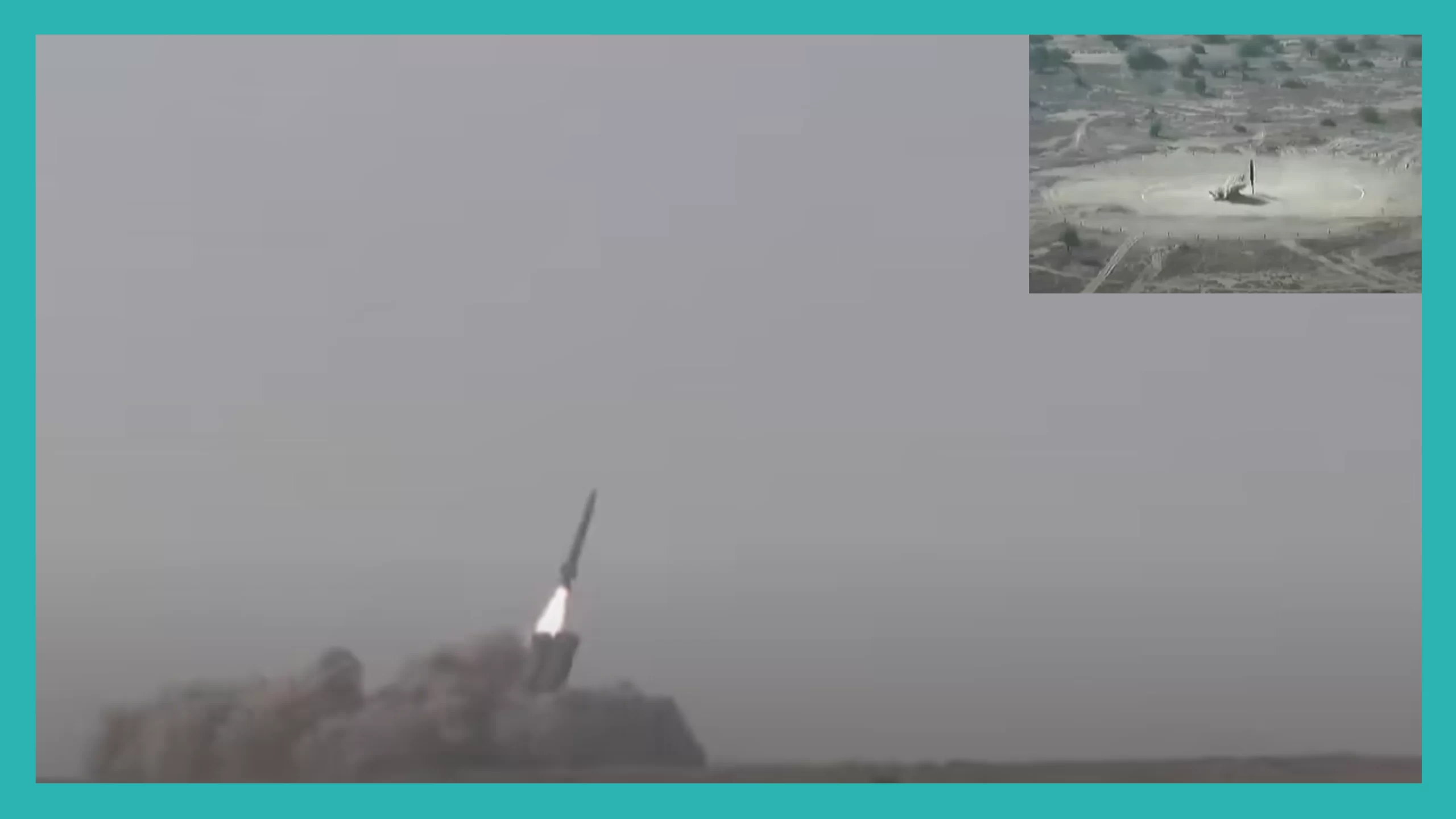

Basically, Pakistan now has an alternative source for procuring modern, functionally adept defence items in China. Not only that, but the Chinese armaments generally cost less to procure than their counterparts from the West. If the Chinese weapons meet the Pakistani military’s requirements, then Pakistan will likely procure them in favour of non-Chinese alternatives, be it Western or otherwise. In fact, the PA’s wheeled self-propelled howitzer (SPH) program is indicative of this fact. The PA had evaluated numerous options, including Chinese, South African, Serbian and others. But ultimately, the Chinese SH-15 won out.

The point at hand is that Pakistan’s defence purchases were likely going to shift more towards the Chinese side, regardless of Islamabad’s ties with the West. The Pakistani military has to operate within a relatively tight fiscal budget for procurement, so it will seek the solution that best optimizes its resources while also achieving key qualitative gains. Traditionally, Pakistan had relied on U.S.-origin arms to achieve that goal.

Basically, American goods – such as the F-16, M109 SPH, AH-1, and others – offered performance, but at an affordable price. The U.S. had fine-tuned its industrial processes to achieve quality and, on top of that, generated economies-of-scale to help control costs.

This was the reason why Pakistan kept pursuing U.S.-origin weapon systems. These weapons let Pakistan gain both qualitative capabilities and scale-up from a quantitative standpoint. Thus, the Pakistani armed forces were happy to heavily invest in those systems. The F-16 program, for example, would have involved over 100 F-16s under the Peace Gate program with an option for another 50.

However, many of today’s U.S.-origin and Western European weapons do not offer that level of scalability for Pakistan. Yes, Pakistan would certainly get qualitative gains by sourcing from the West, but in light of its current economic conditions, it cannot afford Western systems in large numbers. Even if Pakistan did procure some Western weapon systems, the workhorse equipment would still come from China.

Today, China is the only other country that succeeded in replicating the ‘American model’ of developing high-tech systems and generating enough scale to control costs. While China is still trailing behind in some key areas to the U.S. and Western Europe, in other areas, like drones, Beijing could be ahead. But by and large, China’s hardware draws in contemporary technology and works within modern warfare doctrines.

Thus, it is no surprise that Pakistan would look to more Chinese arms. Simply put, it was only a matter of time. The quality and technology have caught up, and the economics of procuring those weapons are favourable. In fact, one can expect other countries to follow Pakistan’s example, such as Algeria (which had traditionally relied on Russian arms), Egypt, and others across the Middle East and Central Asia.

From a geo-strategic standpoint, Pakistan’s concern should not be whether it is relying more on China at the result of shopping less from the West. Rather, Pakistan should understand that national interests are not static. Countries will always change how they deal with other states. In some cases, the shifts can be frequent (e.g., Pakistan’s ties with the U.S.), and in others, more stable (e.g., Pakistan’s ties with China).

However, these relations can always change. Thus, Pakistan ought to work on ways of building permanent anchors for its national security interests. In other words, Pakistan should start investing in its own critical industries, such as gas turbines (which are critical for engines). Granted, programs of this nature will not materialize for decades, but not starting them would leave Pakistan in a perpetually dependent state for these inputs. In fact, Gen. Bajwa implied that the Germans had previously agreed to supply the engines, but they reneged late into the process. Thus, one cannot take these matters for granted.

It seems that Pakistan is starting to take these steps. For example, there are reports of Pakistan designing its own AESA radars for both airborne and surface-based applications. Granted, Pakistan does not have a semiconductor industry; thus, it is likely relying on a foreign source for the critical inputs. But by designing the radar, Pakistan is taking control of the technology stack up the channel. It is learning how to produce the end product using commercially-off-the-shelf (COTS) inputs. This is a step in the right direction. It can now understand how to produce the end solution; thus, if one supplier fails, Pakistan can work with an alternate vendor. Pakistan seems to be taking a similar journey with the Jinnah-class frigate program.