In the 1990s, the Pakistani military began leveraging its defence industry entities to drive arms exports, albeit, as a secondary goal behind the primary objective of supporting domestic requirements.

Nonetheless, by setting up recurring events like the International Defence Exhibition and Seminar (IDEAS) and organizations like Global Industrial & Defence Solutions (GIDS), Pakistan built the commercial venues and infrastructure for marketing and selling arms.

To date, these efforts have not generated the export volumes Pakistan initially anticipated, and big-ticket orders were few and far between. However, despite the lack of traction up to this point, wider shifts across military technology and doctrine could create lucrative niches for the Pakistani defence industry.

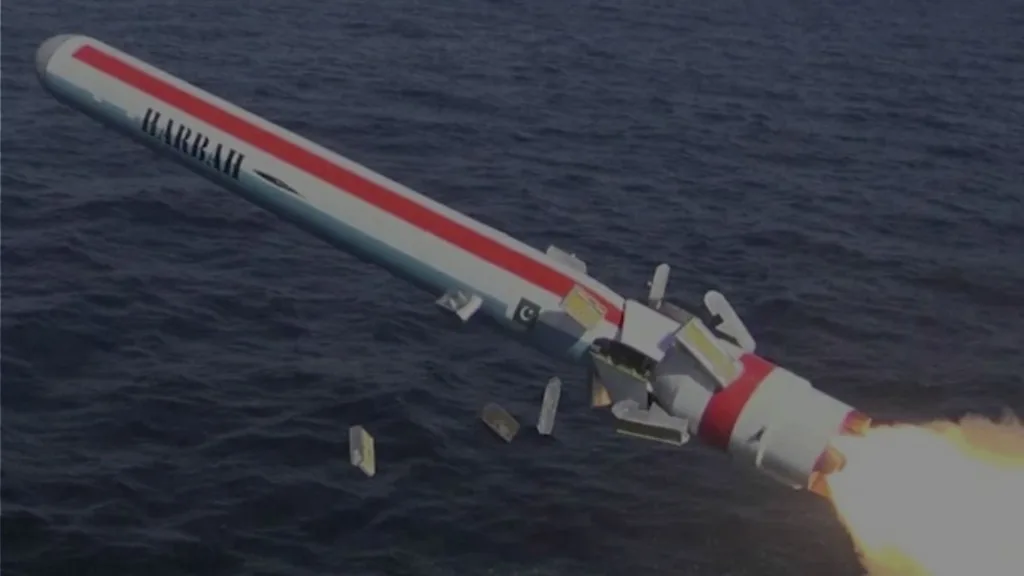

These potential niches include, among others, the rise of loitering munitions, precision-guided bombs and missiles, and custom integration services. While these niches may not draw the attention a fighter aircraft or surface warship sale would, they are in wide demand globally and, if Pakistan executes well, can drive hundreds of millions of dollars in defence exports annually.

Stay up to date with the latest Pakistani defence news with reliable research and accurate forecasting

Click Here

Granted, Pakistan is not sourcing every critical input indigenously. However, the nature of cruise missiles and other guided munitions is that the inputs are, by design, meant to be low-cost and disposable. Thus, even if Pakistan is importing them, it still has significant pricing room to charge for value-added services, such as the munition design and manufacturing stages. Moreover, because countries need munitions in large numbers and (when engaged in conflict) frequently, there are more opportunities for contracts.

Finally, a munition is a lower-risk purchase compared to a fighter aircraft. Thus, there is less of a delta or gap for Pakistan to overcome to pursue such sales, even from non-traditional buyers. Interestingly, this is also a case where diversification is necessary; thus, countries looking to secure multiple supply chains for munitions could be willing to involve Pakistan, even if they themselves already buy from the West.

In the long-term, steering exports towards munitions also helps with generating scale. Pakistan itself will continuously need large numbers of munitions, giving both state-owned and private-sector actors alike the comfort that their production overhead will continue seeing use. Moreover, the incentive to indigenize even further will match with the country’s industrial capacity. So, as Pakistani producers aim to take on more of the value in each contract, they will invest in producing more of the inputs locally, especially as the gap to do so is not as significant as say a turbofan for a fighter or diesel engine for a tank.

Custom Integration Work

Arguably, one of the less celebrated – but potentially lucrative – aspects of Pakistan’s defence industry is its expertise in designing and managing original projects.

For example, Stingray Technologies, which is among the companies represented by GIDS, produces a tactical data link (TDL) system for the Pakistan Navy called ‘Link Green.’ While the hardware inputs – like the software defined radios (SDR) – are imported, the work to design, configure, and deploy a functional TDL was done indigenously. Now, Pakistan is marketing this solution for export.

Don't Stop Here. Unlock the Rest of this Analysis Immediately

To read the rest of this deep dive -- including the honest assessments and comparative analyses that Quwa Plus members rely on -- you need access.