4799Views 0Comments

ICUBE-Q: A Step Forward for Pakistan’s Space Program?

Bilal Khan

Founder of Quwa, Bilal has been researching Pakistani defence industry and security issues for over 15 years. His work has been cited by Pakistan's National Defence University (NDU), the Council of Foreign Relations, Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, Centre of Airpower Studies and many others. He has a Hons. B.A in Political Science and Masters of Interntional Public Policy from Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada.

On 03 May, China launched its Long March-5 heavy-lift launch vehicle from the Wenchang Space Launch Site in Hainan, a tropical island located in southern China. The vehicle was carrying the Chang’e-6 lunar probe, which has the mission of acquiring samples from the far side of the Moon. The Chang’e-6 mission is the world’s first attempt to acquire samples from the far side of the Moon.

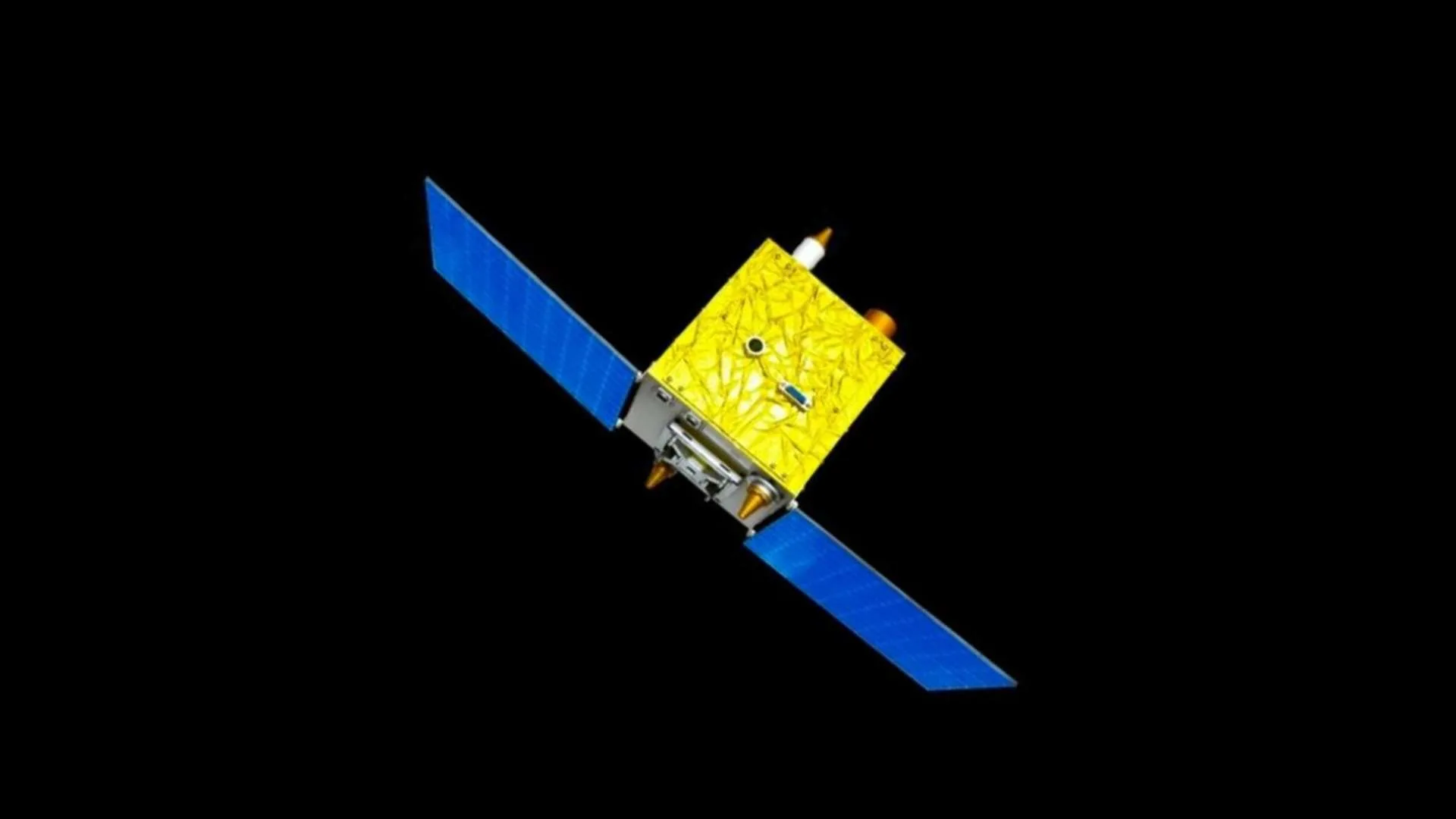

However, the Chang’e-6 was also accompanied by payloads from a number of other countries, including Pakistan, which sent its ICUBE-Q (Qamar). The ICUBE-Q is a miniature satellite jointly developed by the Institute of Space Technology in Islamabad and the Space & Upper Atmosphere Research Commission (SUPARCO). When it enters lunar orbit, the ICUBE-Q will carry out several missions aimed at collecting data about the moon’s magnetic field and taking photos of the Chang’e-6 lunar orbiter.

IST and SUPARCO developed the ICUBE-Q in 14 months. In light of the tight mass restrictions, IST and SUPARCO had to limit the ICUBE-Q’s weight to around 7 kg. It will have a lifespan of three months.

Though not as groundbreaking as India’s lunar programs, the ICUBE-Q was initiated to nurture Pakistan’s skilled labour pool for developing space-based applications in the future. Granted, Pakistan is likely not as serious as India, China, or other countries in terms of space research as a science endeavour, and in that sense, it will always remain behind others. However, the Pakistani armed forces have clearly voiced their requirements for satellites for communications, imaging, and, potentially, navigation purposes.

Off-the-shelf procurement will drive Pakistan’s satellite requirements in the near-term, but at some point, domestic production must materialize for Pakistan to sustain its space capabilities. While a modest step, the ICUBE-Q could contribute towards Pakistan’s space development infrastructure.

Background: Space Vision 2040

In the early 2010s, Pakistan had originally committed to a long-term development program designated “Space Vision 2040.” The Chairman of SUPARCO at the time, Major General Ahmed Bilal, stated that SUPARCO would “make, produce, and launch” domestically built satellites.

By 2020, Pakistan was to have deployed at least three remote-sensing satellites. Thus far, Pakistan has only one such satellite in orbit, the Pakistan Optical Remote Sensing Satellite 1 (PRSS-O1), which was launched by China in July 2018. With a service life of seven years, the PRSS-O1 will reach the end of its lifecycle in 2025; thus, for Pakistan to maintain its remote-sensing capabilities, it will need to replace PRSS-O1 with a new satellite. This new system may be the PRSS-O2. In addition, Pakistan also has a communications satellite called the PakSat-1R, which will reach the end of its lifecycle in 2025 or 2026.

In 2021, the Government of Pakistan sought to allocate funding to study the feasibility of developing the PRSS-O2, a Pakistan Remote Sensing Synthetic Aperture Radar Satellite (PRSS-S1), and the Pakistan Multi-Mission Communications Satellite (PakSat-MM1R). In addition, the government also set funds aside to study the feasibility of space development infrastructure, notably the Pakistan Space Center (PSC) as well as a spaceport, which alludes to the induction of satellite launch vehicles (SLV). There had also been a study for a national satellite navigation system, the Pakistan Satellite Navigation Program (PSNP).

Given Pakistan’s checkered history with aerospace development initiatives (most notably Project AZM), skepticism towards the PSC and spaceport’s viability is valid. That is why one should separate satellite acquisition requirements from developmental aspirations. Each of Pakistan’s military service arms now require various satellite-based capabilities; hence, Pakistan will acquire satellites in this decade, albeit through off-the-shelf purchases and not homegrown development.

Urgent Requirements will Drive Near-Term Satellite Procurement

Pakistan has two satellites that will need replacing in 2025 to 2026 – i.e., the PRSS-O1 and PakSat-1R. With the Pakistan Army (PA), Pakistan Navy (PN), and the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) increasingly moving towards the use of drones at beyond line-of-sight (BLoS) ranges, stand-off range weapons (SOW), and satellite-enabled networking and communications, the armed forces have urgent satellite requirements.

Satellite Communications (SATCOM)

The Pakistani military has a growing number of SATCOM applications. First, the PN is moving ahead with connecting its air and surface assets to SATCOM for communications purposes. Second, the PA, PN, and PAF are each leveraging drones at BLoS ranges, which will necessitate SATCOM for remote operators as well as providing real-time sensor feeds to distantly located command-and-control (C2) centers.

End of excerpt (718/1421 words)

Log in or subscribe to read the rest of the article

Note: Logged in members may need to refresh the article page to see the article.