3031Views 5Comments

Is it finally the Pakistan Navy’s turn?

03 October 2015

By Bilal Khan

Compared to its sibling service arms, i.e. the Pakistan Army (PA) and Pakistan Air Force (PAF), the Pakistan Navy (PN) is, to put it politely, under-appraised. It is not that the Navy is not appreciated, but few seem to fully understand its importance in being the protector of Pakistan’s coasts and the guardian of the country’s sea lines of communication (SLOC). SLOCs are basically key maritime routes connecting ports for sea-trade and naval activity. In other words, the Navy’s worth is undervalued.

A quarter of Pakistan’s gross domestic product (GDP) is dependent on Karachi, the country’s leading commercial port and its largest city. Not only that, but with the planned rise of Gwadar, the country’s dependence on sea-trade (as well as that of China’s should the China Pakistan Economic Corridor or CPEC come to fruition) will only grow. In fact, any outcome that involves Pakistan becoming economically stronger and capable of trading on the global market will require a strong seafaring service arm.

However, in light of today’s problems and tomorrow’s challenges, can we with absolute certainty say the Pakistan Navy is in a position to overcome the currents facing it?

From a high-level view, it is abundantly apparent that the qualitative and quantitative gap between India and Pakistan is the widest (favouring India) in the realm of naval development. While it is true that India has a much larger coastline to defend, it is also a reality that its immediate naval problem (minus whatever ambitions Delhi may have in the Pacific) is Pakistan. In other words, in conflict, it is very likely that a significant portion of the Indian Navy will be available for fighting Pakistan.

While it is true that India is poised to operate multiple aircraft carriers as well as a strong fleet of destroyers, frigates and submarines in the future, it is worth noting that a 1:1 match-up with the Indian Navy (IN) is not necessary for the Pakistan Navy (in the defensive context). The overall capabilities of the PN as well as of the PAF need to reach a conventional threshold where Indian attempts at blockading Karachi (and Gwadar) become exceptionally risky and unfeasible.

One only needs to look at one of the brutally hard lessons Pakistan had to learn in 1971 (and there were many, with the most obvious one being the secession of East Pakistan and the birth of Bangladesh). India’s naval operations off the seas of both East Pakistan and West Pakistan were an unqualified success. India’s combined naval operations resulted in Karachi no longer being able to send out or receive merchant ships, thereby disabling Pakistan’s capacity to trade goods or receive supplies by sea.

Upward Littoral Defence Capability

The Navy’s littoral (i.e. sea that is close to the shore or coast) defence capabilities are improving at an expected and sufficient rate. It is easy to underestimate the importance of littoral defence, but one only needs to look back at the lesson Pakistan learned during the War of 1971 with India. In an engagement (Operation Trident) the Indian Navy (with the use of anti-ship missile equipped boats no less) attacked the port of Karachi and destroyed the destroyer PNS Khaibar and damaged the destroyer PNS Shah Jahan beyond repair. The Indian flotilla also destroyed fuel storage tanks at the harbour as well.

It goes without saying that Pakistan cannot leave its littoral environment open to such attacks ever again. With that goal in mind, the Navy had steadily built its littoral defence capabilities through the induction of numerous types of fast-attack crafts (FAC) capable of using anti-ship missiles (or AShM – be sure to check out Quwa’s overview of the technology).

The first of the more modern acquisitions came in the form of two MRTP-33 FACs from Turkey. The MRTP-33 was designed and built by the Turkish shipbuilder Yonca-Onuk. The 120 ton MRTP-33 is equipped with a 30mm gun and is also capable of carrying four AShMs. It can travel in-excess of 47 knots at full-load (Yonca-Onuk).

As is obvious from the aesthetic qualities of the FAC, the MRTP-33 was designed to be difficult to observe and track on radar. It was designed on the idea of reducing radar and heat-signatures, thereby making it more elusive and a threat to larger ships.

In addition to the MRTP-33 the PN is in the process of inducting four Azmat-class patrol boats, a Chinese design built locally at Karachi Shipyard and Engineering Works Limited (KSEW) under a transfer-of-technology agreement. Similar to the MRTP-33, the Azmat-class was designed around low-observable concepts, but is a heavier ship (at 560 tons). Its top speed is 30 knots (KSEW).

According to Jane’s the Azmat-class can be armed with eight 180km range C-802A AShMs and is equipped with a Type 347 fire-control radar, twin 30mm forward mounted guns, two 12.7mm machine guns, and a AK-630 close-in-weapons-system (CIWS) for self-protection against incoming missiles. It is a complete package in as far as small littoral combat ships are concerned.

It is not clear how much further the Navy will go in building its FAC fleet. There was a report from a Chinese media outlet claiming that Pakistan would acquire as many as six Type-022 catamaran FACs (Defense News). In addition to being able to carry eight AShM, the Type-022 could also be equipped with a short-range air defence (SHORAD) system. There was also a report in early January 2015 from Defense News where Usman Shabbir, an analyst of the Pakistan Military Consortium think-tank, suggested that Turkey’s Yonca-Onuk could offer a larger FAC design based on its MRTP-series.

Based on these two reports, it would seem that there may be room in the PN for a FAC design that is not only capable of effective anti-ship warfare (AShW), but also SHORAD (using a short-range surface-to-air missile system) and possibly even anti-submarine warfare (ASW). Having all three capabilities in one platform would certainly not result in a small design, but a sub-1000 ton could be an effective bridge between the PN’s light littoral defence crafts and its much larger seafaring frigates. Alternatively, the PN could simply focus on drawing out a larger number of 120 and 250 ton FACs such as the MRTP-33 and Type-022, respectively.

That said, the idea of having a bridge between FACs and full multi-mission frigates (FFG) was the apparent vision behind the Navy’s now-shelved plan of acquiring a modern corvette. A corvette basically sits between (in size, range and capability) frigates and fast attack crafts. Corvettes enable navies to have ships that can serve as solid defensive war-time assets as well as effective SLOC patrol and management ships in times of peace.

Up until the advent of President Zardari and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Navy had intended to acquire four multi-mission corvettes through a joint-program with Turkey. The program was to be based on the MILGEM design, and while regulatory issues in Turkey put a dampener on that project, the fact of the matter is the Pakistan Navy did not have the funds to pursue a viable alternative (for example the French DCNS Gowind-series or TKMS MEKO). Again, it is unclear if the corvette program will be revived, but if so, then the Navy has a number of options, including Chinese ones.

A robust multi-mission design capable of housing eight AShM, two triple ASW torpedo launchers, a point-defence missile system (PDMS) for protection against incoming missiles, and/or a short- range surface-to-air missile (SAM) system (akin to Umkhonto and MICA-VL) would be interesting. If costs are kept within reason, such a design could be an excellent means for the PN to complete the surface element of its littoral defence capabilities, especially in terms of ASW (to protect vital assets from enemy submarines). These ships could also serve in the role of off-shore patrol vessels (OPV) in peacetime, which would enable the Navy to protect the SLOC from piracy, smuggling and other maritime crimes.

I am not sure if this is something that will be pursued in the short or medium-term. In fact, I do not expect the Pakistan Navy to concern itself about corvettes and OPVs until it has its frigate, submarine and aviation requirements settled. How long that will be is an entirely different story, but until then, I expect the littoral fleet to be reinforced with additional FACs in the vein of MRTP-33 and the Azmat-class.

Emerging Underwater Ambition

One of the Pakistan Navy’s clearest and perhaps most achievable areas of modernization and in fact growth are in regards to its submarine fleet. At present spearheaded by 3 modern French DCNS Agosta-90B (Khalid-class) and supported by 2 Agosta-70 (Hashmat-class) submarines, the Navy has spent the past 10 years in search for ships to replace its now retired Daphne and ageing Agosta-70 diesel-electric submarines (SSK).

In 2008-2009 it was very close to finalizing a deal with Germany’s ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems (TKMS) for the sale of 3 Type-214 submarines, which would have been built in Pakistan. What essentially scuttled the program was Pakistan’s economic woes which required ‘support’ from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which in turn mandated deep austerity cuts (which hit military modernization programs quite hard). In addition, 2008-2009 also marked a major escalation in the internal conflicts plaguing northwest Pakistan (which continue to this day).

In 2011 it was reported that the Pakistan Navy was in talks with China Shipbuilding & Offshore International Co. Ltd (CSOC) “to jointly design and build six aid-independent propulsion (AIP) submarines” (Defense News). Four years ago this was fairly significant news, not just in terms of Pakistan buying Chinese attack submarines (a departure for the Navy given that it exclusively operates Western systems), but the suggestion that Pakistan could acquire air-independent propulsion (AIP) systems from China.

AIP technology basically enables non-nuclear submarines to operate underwater without snorkeling (i.e. surfacing to access oxygen) for significantly longer periods of time (potentially multiple weeks at a time) than regular diesel-electric submarines. AIP technology also allows conventional submarines to operate more quietly as well, which is a vital benefit in underwater combat where detection is based on acoustics (i.e. sound). Pakistan’s Agosta-90Bs are equipped with AIP systems as well, i.e. the MESMA (Module d’Energie Sous-Marine Autonome), which is based on France’s nuclear propulsion technology, but dependent on ethanol and oxygen.

In April 2015 the Government of Pakistan reportedly approved the purchase of eight new submarines to built in China, but the type and price had not been revealed (Defence News). It is more than likely that the type is based on the S20, which in turn seems to be based on the Type-039/041 Yuan-class diesel electric submarines in service with the People’s Liberation Army Navy (IHS Jane’s 360). It is possible that the submarines will be equipped with Stirling engines, another form of modern AIP technology (IHS Jane’s 360).

While it is expected that the Pakistani submarines will be equipped with the standard anti-ship warfare (AShW) and anti-submarine warfare (ASW) capabilities, likely in the form of YJ-82/C-802 and Yu-3/Yu-4 torpedoes (IHS Jane’s 360), respectively, it is not clear whether they will be equipped with the capability to launch submarine-launched cruise missiles (SLCM), which in turn could be equipped with light plutonium-based nuclear warheads.

The ability to launch SLCMs in the form of say the Pakistani Babur land-attack cruise missile (LACM) would enable Pakistan to achieve assured nuclear second-strike capability. “Second-strike” is the ability to respond to an enemy’s successful use of its nuclear weapons on one’s soil, and “assured” second-strike is the absolute ability to do so regardless of the situation on the ground (e.g. if numerous if not all land-based nuclear launch sites and/or warhead-stocks are destroyed). The availability of as many as eight submarines with SLCM capability will allow Pakistan to complete its nuclear-strike triad, i.e. the capacity to deploy nuclear warheads from the surface (land or sea-surface), air (through aircraft) and underwater.

In July the contract was reportedly finalized and referred to the Chinese government, upon whose approval the deal will be formally inked. It is unclear what the value of the deal is, though the Financial Times suggested that it could be worth as much as $4 to $5 billion U.S. The Express Tribune added that the Pakistani government would pay for the program through four installments.

I do not think the deal for the submarines is worth that much as it would amount to a whopping $500 million to $625 million a submarine, which I think is pretty close to the price of Western submarines. Granted, the strong likelihood of these submarines being built in Pakistan and the reality that it will be financed can amount to higher overall costs, but still, this is too high. I am more inclined to adopt the view of Pakistan Military Consortium’s Haris Khan, who put the figure at $250-350mn a unit (Defense News).

That said, I do think the $4-5bn figure has merit in the sense that it could be the cost of a holistic naval package. A commercial Chinese media outlet (so take it with a grain of salt) alluded to this idea as well by reporting that the PN would order six Type-022 FACs and 4 “improved” F-22Ps. Thus, I think it is possible that Pakistan will order not only submarines from China, but potentially even modern multi-mission frigates, an area in need of massive improvement in the Navy.

Defense News reported that the Pakistan Navy is also looking for surplus submarines from the West, namely France, Germany and the U.K. But the author, Usman Ansari, detailed that acquiring surplus units directly from the West is unlikely, though Pakistan might be able to acquire Turkish Navy Type-209/1200 SSKs. According to Haris Khan, the surplus submarines are being pursued to replace the aged Agosta-70 SSKs currently in service with the Navy. I am also interested in seeing if the Navy would ever consider smaller coastal submarines (in the vein of the French DCNS Andrasta or German Type-210mod) for use in littoral defence and special forces operations (replacing the MG 110 midget submarines currently in service).

Definitely in Need of More Ships

The Pakistan Navy’s core surface fleet is composed of four new Zulfiqar-class (i.e. F-22P) multi-mission frigates, five heavily aged Tariq-class (i.e. Amazon-class or Type-21) frigates, and one old but reasonably capable Alamgir-class (i.e. Oliver Hazard Perry-class or FFG-7) frigate.

Of these ships, the F-22P is the modern system, equipped with eight AShM, two triple-cell ASW torpedo launchers and a short-range surface-to-air missile (SAM) system (of up to 5km). The F-22Ps were ordered from China and are based on the Type-053H3 design, but with improvements to the design enabling for a lower radar cross-section (RCS), i.e. reducing its detectability on radar. That said, relative to the reality of modern naval warfare, the ships are limited in some key respects, namely in their anti-air warfare (AAW) capabilities. Yes, the F-22P is a good AShW and ASW system, but its AAW sub-systems do not give the Navy the coverage it needs to stop key aerial threats such as enemy fighter aircraft or maritime patrol aircraft (MPA).

This is a very important point. While it is true that the balance of offensive operations can be carried out by submarines equipped with LACM and AShM, one must be mindful of the threats posed to submarines. MPAs such as the Lockheed Martin P-3C Orion and Boeing P-8 Poseidon in service with the Pakistan Navy and Indian Navy, respectively, are designed to track and engage submarines. These are fairly large aircraft capable of loitering in the skies for extended periods of time, and – by virtue of today’s network-centric warfare environment – when coupled with support from friendly frigates, corvettes and even unmanned drones, can be a very serious threat to one’s submarines.

The modern multi-mission frigate, in this context, would be a critical means of defence against these aerial threats. But it is vital that these ships are equipped with sufficient AAW systems, e.g. SAMs with ranges of at least 30km. Today, such missiles are deployed through vertical launch systems (VLS) and paired with long-range radars capable of tracking and engaging multiple targets. It is unclear whether the F-22P could be retrofitted to use these sub-systems, but I think the (necessary) inclusion of these systems in the Pakistan Navy could occur through a larger frigate design.

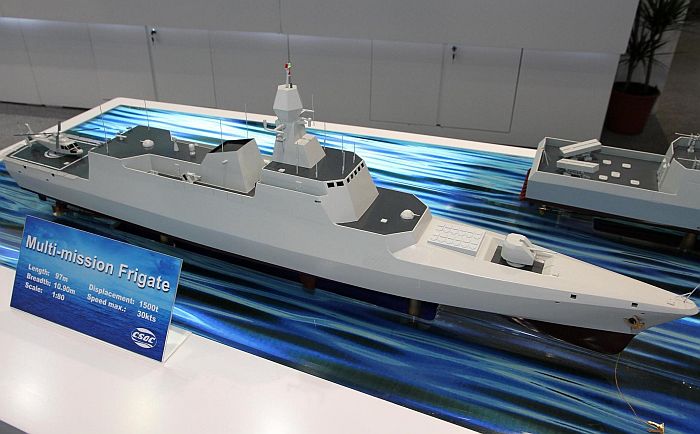

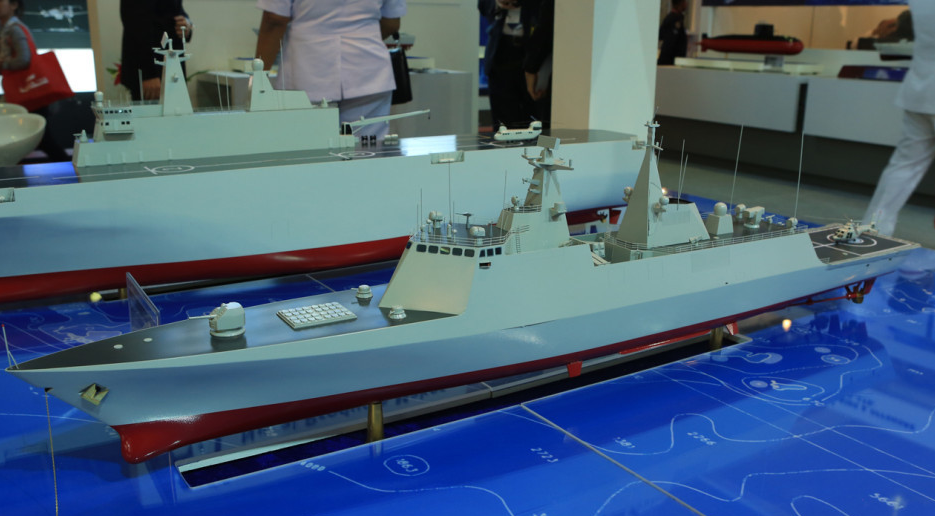

Although the Type-054A design (currently in service with the People’s Liberation Army Navy or PLAN for short) is slotted as a likely choice for the Pakistan Navy, I think it is worth looking at the actual export-centric designs being pushed by China for a more accurate idea. One such ship is from China Shipbuilding & Offshore International Co. Ltd (CSOC) called “High Performance Frigate.” The frigate was designed to have a displacement of 3500 tons and can be equipped 8 AShM, two triple-cell ASW torpedo tubes, a point defence missile system (PDMS) to intercept incoming missiles and as many as 32 VLS cells.

These VLS cells could be used by a medium-range SAM such as the Chinese HHQ-16, the PLAN’s mainstay medium-range SAM system. Alternatively, the Navy could also look at the French MBDA Aster-15, British-Italian MBDA Common Anti-Air Modular Missile (CAMM) or (if a new frigate program enters the pipeline after 2020) the in-development South African Umkhonto-R.

In comparison to the Pakistan Navy’s current surface fleet, the inclusion of six such frigates would be a major force-multiplier. Not only would they be more than suitable replacements for the Type-21 and FFG-7 frigates, but they would greatly improve the Navy’s combat capabilities across numerous areas, not only AAW. While this depends on the size of the VLS cells, but the PN could theoretically use a new frigate program as a means to deploy a specially-modified Babur LACM, fully extending Pakistan’s strategic strike capabilities to the maritime theatre, both underwater (via submarines) and on the surface.

As I had noted earlier, the reported $4-5bn figure covering the China-Pakistan submarine deal may have merit, but if taken in the context of possibly including frigates. Four to six truly modern and fully capable multi-mission frigates along the lines of what I had described above can fit within the reported figure.

Broadening the Wings

Pakistan’s maritime aviation development has seen a fair bit of development over the past decade. You will notice that I did not specify the Pakistan Navy, and there is a good reason for that. The maritime aviation theatre in Pakistan is shared between the Pakistan Navy and the Pakistan Air Force (PAF). The former has built a strong fleet of maritime patrol aircraft (MPA) and utility helicopters, the latter has been in the process of bolstering its fighter and surveillance aircraft fleets in the area.

The Navy inducted seven surplus Lockheed Martin P-3Cs and upgraded two in-service frames to P-3C Update II.5-standard (Defense Industry Daily). The Navy was supposed to have nine P-3Cs, but two were destroyed in an attack on Pakistan Naval Station Mehran in May 2010. Pakistani P-3Cs are capable of anti-submarine warfare (ASW) and anti-ship warfare (AShW) through the use of lightweight air-launched torpedoes and anti-ship missiles (the Pakistan Navy has AGM-84 air-launched Harpoon Block-II AShMs), respectively. These aircraft basically serve as the backbone of Pakistan’s long-range maritime patrol fleet.

In recent years the Navy has been in the process of inducting two new MPAs in the form of the ATR-72-500 (Plane Spotters), for which $294mn had been requested in April 2015 from the Pakistani government to commence airframe modifications and upgrades (Defense News). Given the model-type of these ATR-72s, it is likely that the Navy will have them converted into ASW MPAs, though it is possible that subsequent orders might involve the ATR-72-600, which will allow for AShW capable platforms as well (Finmeccanica). Given the cost-effective nature of the ATR-72-500/600 (relative to its capabilities), I think the Navy will build its ATR-72 MPA fleet up incrementally over the coming years. These may ultimately replace the Fokker F27s currently in service.

In tandem with the F-22P frigates, the Navy ordered six Harbin Z-9EC ASW helicopters from China. The Z-9 is a Chinese license-built variant of the French AS365 Dauphin utility helicopter. The Z-9EC can be equipped with an ET-52C torpedo (a Chinese-built derivative of the Italian A244-S light torpedo), enabling its host frigate to engage a submarine that is too far for its own ASW torpedoes (or to help it engage multiple submarines simultaneously in its vicinity).

The Navy also has six Westland Sea King helicopters serving in the multi-mission role of AShW, ASW, search & rescue (SAR) as well as general utility (e.g. transport). These, alongside the Aerospatiale Alouette III, are the older helicopters in the Navy’s fleet. These will eventually need to be replaced, but it is not known exactly what will replace them given that the Navy has yet to (publically) pursue successors. I think the Alouette IIIs will most likely be replaced by additional Z-9s from China.

The Sea Kings on the other hand, it is difficult to say what the PN might opt for in the end. One increasingly popular successor is the European NHIndustries NH-90, but it is an expensive helicopter. On the other hand, given that the Navy does not operate a large number of utility helicopters, it is conceivable it could fund a small number of NH-90s to directly replace the Sea Kings (i.e. six or so helicopters). For example, New Zealand ordered 8 NH-90 for about $306mn in 2006. Alternatively, the Navy could also wait for China to successfully complete the development of its Z-20 medium-lift helicopter (which seems to be in the same general category as the NH-90).

In addition to the Naval Air Arm, the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) is also active in the maritime theatre. Alongside an existing squadron of Mirage 5PAs equipped for AShW through Exocet AShMs, the PAF Southern Air Command is also in the process of inducting a JF-17 squadron capable of using C-802A and CM-400AKG AShMs. It is also possible that a Karakorum Eagle (aka ZDK03) Airborne Early Warning and Control (AEW&C) aircraft has also been assigned to Southern Air Command (Defense News) as well, enabling the region to have strong airborne surveillance and command and control capabilities (especially if the Link-16 data-link system is integrated atop of the PAF and PN’s numerous assets).

An interesting side-note. The Pakistan Navy requested 3 P-3 aircraft equipped with Hawkeye 2000 AEW suites in 2006, but the deal never reached fruition. It is unknown if the Navy will seek to renew its efforts to acquire AEW&C assets. On another side-note, there are the rumours regarding the PAF allegedly pursuing Su-35, and while these rumours have recently been struck-down by Denis Alipov (the Deputy Chief of Mission in the Russian Embassy to India in New Delhi), it seems the PAF may indeed be looking for longer-range twin-engine fighters to augment its maritime needs (IHS Jane’s 360). How that might materialize however is anyone’s guess.

So, is it finally the Pakistan Navy’s turn?

Do note that this piece is not in any way an exhaustive or complete review of the Pakistan Navy’s current fleet and inventory nor of its acquisition plans. I personally consider it a very broad overview aimed at providing an overall but surface-level understanding of the Navy’s actual acquisition plans and ideal acquisition routes. In the end however it is important to appropriately value the significance of the Pakistan Navy in terms of the country’s geo-political and economic realities. The Arabian Sea is Pakistan’s bridge to the Arabian Gulf, a key zone for the country’s current economic needs and future commercial prospects, to have it (and the livelihoods of tens of millions of people) cut-off in times of war (again!) would be a travesty. It is the Pakistan Navy’s mission to protect Pakistan’s coasts, but it cannot do so if it is left to manage an increasingly massive quantitative and qualitative gap with India.

Read More on the Pakistan Navy’s Modernization Plans:

5 Comments

by Shahzad Masood Roomi

Superb piece …. like always. Can I repost it on my blog along with your name and link of this website page?

by saqrkh

By all means 🙂

by Guest

Kindly post an in dept piece on PN and PAF’s AWACS and MPAs.

What is the main role of these aircrafts, like how are they different from each other? and why cant they be combined so that the Navy just has one aircraft to take care of both the jobs.

Why is PN inducting 2 types of MPAs?

How is the P3 compared to P8? I mean what does the PN lack in that the IN might have an advantage in by having the P8.

Why is PAF inducting 2 types of AWACS?

Finally how many MPAs and AWACSs does Pakistan need to secure its Airspace and Waters?

by Sami Shahid

Pakistan Navy should now go for JF-17’s , more fast attack crafts and submarines.

by WARRIOR

That merhan base attack was controlled by RAW

Like most terrorist activities in Pakistan