1899Views

Sealing the Afghan-Pakistan Border – A Case Study

Author Profile: Syed Aseem Ul Islam is a Research Scholar at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA, specializing in adaptive and model-predictive flight control systems. He received his bachelor’s degree in aerospace engineering from the Institute of Space Technology, Islamabad, and his master’s and Ph.D. degrees in flight dynamics and control from the University of Michigan.

With the withdrawal of the United States from Afghanistan imminent there is a serious concern among Pakistani planners about the effects of the situation in that country spilling over into Pakistan.

The concerns are two-fold: First, preventing terrorist groups that may find safe haven in Afghanistan from crossing the border into Pakistan. Second, preventing an influx of refugees in response to a possible civil war in Afghanistan.

This is made clear by Prime Minister Imran Khan’s interview to the New York Times where he is quoted to have said:

“What if [the] Taliban try to take over Afghanistan through [the] military? Then we will seal the border, because now we can, because we have fenced our border, which was previously [open], because Pakistan does not want to get into, number one, conflict. Secondly, we do not want another influx of refugees.”

It is becoming increasingly likely that we will see a Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, followed by civil war.

Of course, the Pakistani state has been aware of this possibility and has made efforts to mitigate its effects. The much-touted border fence is mostly complete, with statements that it would be completed by June 30th.

Ignoring the improbability of the fence being completed so quickly, a border fence on its own cannot “seal” the border. The border fence (like any other barrier) can only slow someone from crossing. For this reason, forts have been planned along the fence.

To investigate the dynamics of an illegal border crossing, let us assume some parameters.

Firstly, the fence must be cut or overcome in some way. Let us consider that this process can be done as quickly as 10 minutes by a motivated crosser.

Secondly, the border will be crossed on foot or with assistance by animals or off-road vehicles, and thus, the crosser will enter Pakistan at an average speed of 40 km/h.

This scenario gives us a time of 15 minutes before the person crosses 10 km inside Pakistan (and thus, will be too difficult to find, track, and intercept)

To stop an illegal border crossing, we must detect the crossing within 10 minutes and intercept the individuals that have crossed 15 minutes after they have crossed the border.

Using ground-based forts, the defenders are subject to the same mobility constraints as the crossers – they must travel on poorly built roads or off-road at average speeds of 40 km/h.

With the planned construction of 443 forts, interception of crossers should not be an issue as each fort will manage a border length of roughly 6 km (assuming the entire length of the Durand line even though the fence does not span the entire Durand line).

However, detection of crossings will be a serious capability gap as ground-based surveillance systems cannot see distances as long as 6 km over uneven. The solution to this gap is obvious: unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and this article will provide a case study for surveilling the AfPak border using UAVs.

The Border

We will consider the worst-case scenario and include the entire length of the Durand line for surveillance. We will divide the border into two regions: blue and red.

The blue region will be served by UAVs flying out of Mianwali AFB, which is 147 km from the border.

The red region will be served by UAVs flying out of Samungli AFB, which is 57 km from the border.

We will assume that the UAV bases are on average 100 km from the border.

Since we are dividing the border into two equal parts, we will only consider one half, and the lessons from it would apply equally well to the other half. Considering the Durand line is 2,670 km long, each half is 1,335 km long.

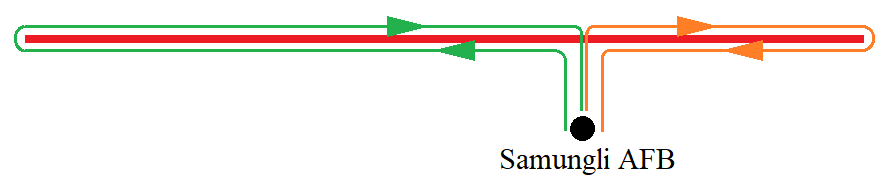

The mission profile for the UAVs will consist of:

- Taking off from the AFB, climbing to cruise altitude, while flying straight towards the border, then either turning 90 left or right.

- Flying along the border till the end of the blue or red region.

- Changing the bearing by 180 and flying along the border again and returning to the location where the border surveillance was started.

- Return to base for landing.

The flightpaths for the red region are visualized below:

Note that the lengths of the green and orange flight paths are smaller than the maximum flight path possible with the UAV that we select below.

The UAV: Shahpar-II

We will propose a capability built upon the recently inducted Shahpar-II UAV for the reason that being an indigenous system, it will be cheaper and faster to produce and induct in numbers…

End of Excerpt (810/1,774 words)

You can read the complete article by logging in (click here) or subscribing to Quwa Premium (click here).