On 26 December 2024, China surprised the world by flying not one, but two, new fighter prototypes embodying its vision for next-generation air systems, the Chengdu J-36 and the Shenyang J-XX/J-50.

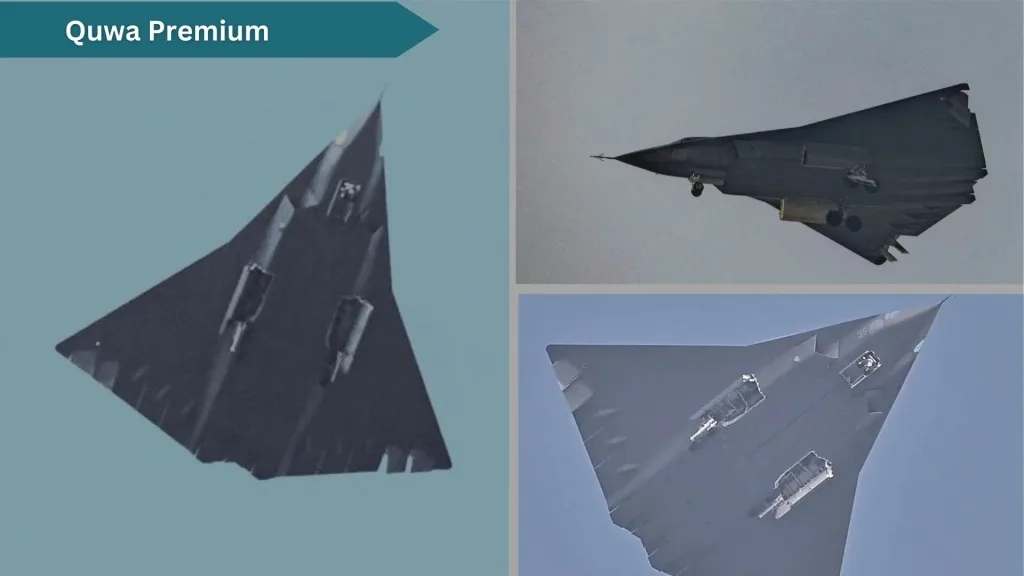

Through a series of controlled leaks, China revealed a relatively large tailless diamond-wing design from Chengdu dubbed the J-36 (based on its airframe number #36011) and a smaller, but still large, tailless “lambda-wing” platform Shenyang (unofficially called J-XX or J-50).

- Bill Sweetman. “Boxing clever? China’s next-gen tailless combat aircraft analysed.” Royal Aeronautical Society. 26 December 2024. URL: https://www.aerosociety.com/news/boxing-clever-chinas-next-gen-tailless-combat-aircraft-analysed/

Ibid.

Ibid.

“China remains coy on its sixth-generation fighter program.” ANI News. 15 July 2024. URL: https://www.aninews.in/news/world/asia/china-remains-coy-on-its-sixth-generation-fighter-program20240715163921/

- Ibid.

Valerie Insinna. “China ‘on track’ for 6th-gen fighter, US Air Force needs to get there first: ACC chief.” Breaking Defense. 26 September 2022. URL: https://breakingdefense.com/2022/09/china-on-track-for-6th-gen-fighter-us-air-force-needs-to-get-there-first-acc-chief/

- Ibid.

Tyler Rogoway. “Tailless Fighter-Like Airframe Spotted at Chinese Jet Manufacturer’s Test Airfield.” The Warzone. URL: https://www.twz.com/42937/tailless-fighter-like-airframe-spotted-at-chinese-fighter-jet-manufacturers-test-airfield

Valerie Insinna. “China ‘on track’ for 6th-gen fighter, US Air Force needs to get there first: ACC chief.” Breaking Defense. 26 September 2022. URL: https://breakingdefense.com/2022/09/china-on-track-for-6th-gen-fighter-us-air-force-needs-to-get-there-first-acc-chief/

Don't Stop Here. Unlock the Rest of this Analysis Immediately

To read the rest of this deep dive -- including the honest assessments and comparative analyses that Quwa Plus members rely on -- you need access.