40Views 1Comment

Pakistan’s C4ISR (Part 4): Communications (Data-Links)

27 March 2016

By Bilal Khan

Part four of our series on Pakistan’s C4ISR [command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance] will focus on the role of communications technology, especially in the context of network-centric warfare (a primary objective of C4ISR). Past sections are also available on our website: Parts one, two and three.

By connecting information from sensors to the correct respondents, communications technology is a vital component to an effective C4ISR system. To understand how or why, just consider the following practical example: An airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) aircraft’s radar (i.e. the sensor) identifies new enemy aircraft entering an area. Through a tactical data-link, the information from the AEW&C’s radar is quickly transmitted to friendly fighter aircraft, enabling pilots to not only have strong situational awareness, but the time and room necessary to formulate a response to the problem.

The above is merely one very specific example, but you will notice that the tactical data-link (or TDL for short) was absolutely essential to enabling a timely response. When referring to “communications” in the context of C4ISR, we are referring to systems such as TDL, which serve as a bridge between the assets that acquire information, and the assets that respond based on that information. Pakistan utilizes numerous TDLs to network its assets. The most notable one is the Link-16, a popular American TDL protocol in use by the Pakistan Air Force (PAF). However, there are others as well, and this will article will attempt to shed some light on them, as well as an understanding of the technology itself.

Understanding Data-Links

Before continuing onto Pakistan’s tactical data-links (TDL), it is important to have a clear understanding of what data-links are and how they are produced. In simple terms, TDLs are the means through which one connects information from sensors (such as radars, sonars, electronic warfare suites, etc) to all those in need of that information. In fact, the objective of TDLs is not ground-breaking or radical; militaries have always sought for a means to bring newly acquired information to the right respondents.

In World War Two, radars were used to detect intruding enemy fighters and bombers, and the information gleaned from radars were conveyed to friendly forces through radioed voice communication. In time, this method (i.e. ground-controlled interception or GCI) was improved through the use of superior radars as well as computational power and visualization of the “picture” presented by the radar. In fact, this process was essentially an early form of data-link connectivity: Sensor information was taken, processed, and displayed to a controller. These controllers, who could be stationed on the ground or even in the skies (via early-generation AEW&C aircraft) relayed this information to friendly fighters, who in turn would use the information to reach their targets (with ample time to prepare and strategize for the confrontation).

In later years, wireless data-capable TDLs – such as Link-16 – emerged as a means to bring the situational picture generated by a powerful radar (such as those found on AEW&Cs) directly to a networked friendly asset. In other words, in addition to guidance from a controller, the fighter pilot (as well as another respondent on the network) could even see the information acquired by the off-board radar on his or her multi-function display (MFD). Modern TDLs such as Link-16 made the voice and data information dissemination process an exponentially quicker process, thereby enabling networked assets acquire situational awareness of the battlefield in a real-time (or at least near real-time) manner.

The basic building block necessary for a modern TDL is a software defined radio (SDR) terminal. For example, Link-16’s SDR is the MIDS-JTRS [Multifunctional Information Distribution System-Joint Tactical Radio System Terminal]. To put it simply, a SDR is a radio where some of its functions (e.g. signal processing) are done through software instead of hardware. This enables users to upgrade their radio sets without necessarily having to make costly hardware alterations. In fact, the cellular radios on consumer mobile phones are voice and data capable SDRs, though not as secure or capable as military-grade SDRs.

A military-grade data-link network requires that SDRs be highly jam-resistant and encrypted. Jamming resistance is typically achieved by having the SDR transmit across a large number of frequencies – i.e. ‘frequency hopping.’ The SDR would transmit at a different frequency with each pulse, making it difficult for an electronic warfare (EW) jammer to confuse the SDR, which occurs by recording and re-transmitting the frequency at which the SDR is broadcasting.

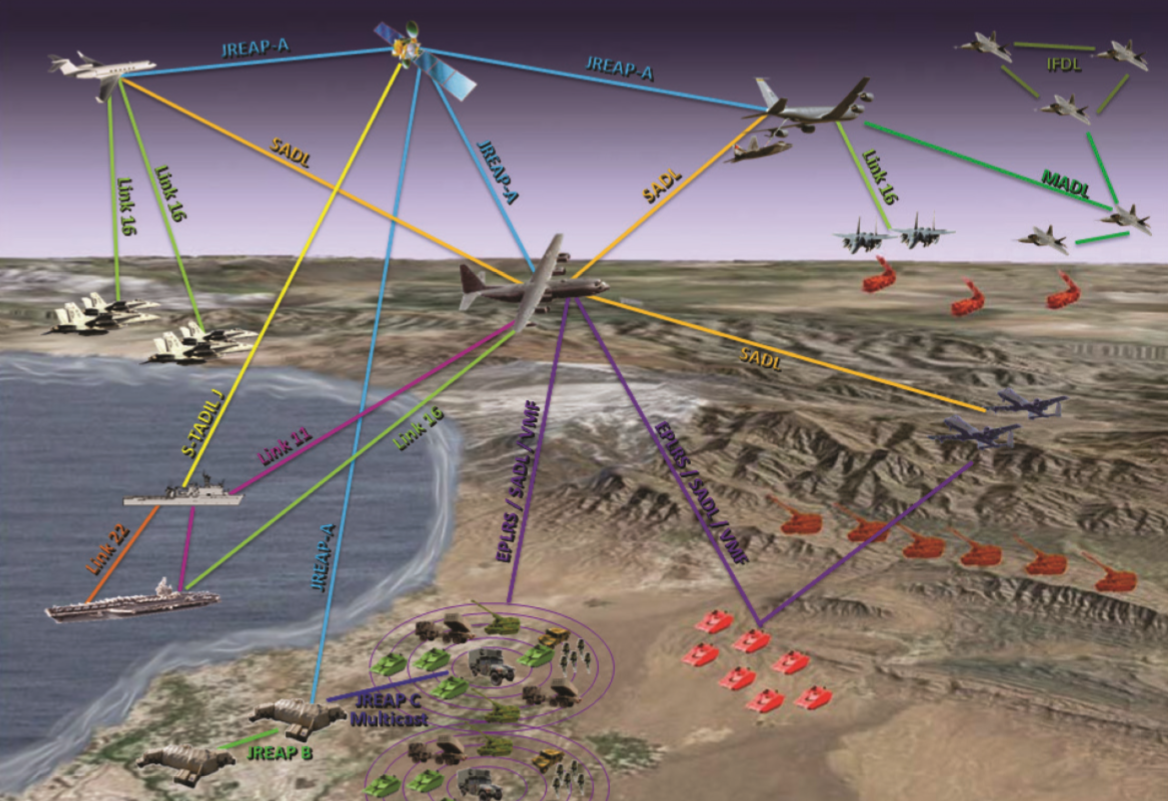

Militaries typically use different TDL networks. For example, Link-16 is popular for use with airborne assets such as fighter aircraft, but there are different TDLs for networking ground and maritime-based assets as well. There is no “universal” network, hence militaries (including the U.S.) are required to formulate ways to achieve interoperability between different assets.

This could be done through equipping certain ‘core’ assets, such as AEW&C, with systems that enable them to operate on different data-link networks. Subsystems, such as multi-link interface units (such as the Finmeccanica MLIU-550), can be used to manage incoming flows from different data-link networks. In turn, AEW&C and other core assets could serve as intermediaries between assets operating on different data-link networks. For example, new information acquired by soldiers on the ground could be transmitted via “Link-A” to an AEW&C, and the on-board controller can verbally convey that information to a fighter operating on “Link-B.” Alternatively, an AEW&C could acquire information from a “Link-C” aircraft’s radar, process it (i.e. de-crypt), and then re-package (i.e. re-encrypt) and transmit it via “Link-B.”

Pakistan’s Data-Links

The Pakistani military makes use of multiple data-link protocols. As details are very scarce, it will not be possible to cover all (or even most) of them, but a look at the Pakistan Air Force (PAF)’s tactical data-link (TDL) usage should offer an idea of how the military’s wider network capabilities function. The PAF’s primary TDLs are the Link-16 MIDS-LVT (Low Volume Terminal) and an indigenously developed solution, which we will refer to as “National Data-Link” (NDL).

The Link-16 is in use with the PAF’s F-16s and the NDL is in use with the JF-17, Mirage ROSE, and – presumably – F-7PG. The earliest official acknowledgement of the NDL occurred in 2010-2011 when the goal of developing an indigenous data-link solution was listed by the Ministry of Defence Production (MODP). By 2015, the system was in operational use on the JF-17. The Link-16 MIDS LVT and NDL are two separate networks, but it is likely that the PAF’s Erieye and ZDK03 AEW&C are being used to bridge them. As discussed above, this could occur by equipping the Erieye and ZDK03 with multi-link interface systems, which would enable them to receive and process information received from each of the networks in use by the PAF (as well as Army and Navy).

The use of data-link networks such as Link-16, NDL and others (such as the systems being used to network air surveillance radars) makes the PAF a true network-centric force. In practical terms, the PAF’s networked assets have the capacity to share and receive vital tactical information in at least near real-time, enabling them to react to emerging situations in a timely manner. Moreover, the availability of the NDL gives the PAF the flexibility to readily network future airborne assets at will, such as medium-altitude long-endurance (MALE) UAVs. The core technological expertise could be deployed to develop data-link solutions for the Army and Navy as well, if not already underway (or achieved). The software defined radios (SDR) used to support Pakistan’s indigenous data-links are sourced domestically and from overseas (from firms such as Harris as well as Rohde and Schawrz).

It will be interesting to see how the Army and Navy’s network-centric capabilities are developed. It is likely that the armed forces will adopt a model similar in concept to what is being deployed in the U.S. In other words, a combination of different networks with numerous ‘core’ assets, such as AEW&C and frigates, to bridge the Army, Navy and Air Force, especially during joint-operations. Perhaps there may even be an analogue to the U.S. Common Data-Link (CDL) system whereby the respective headquarters or command posts of each service arm can communicate and exchange real-time (or near real-time) data.

To further cement its network-centric nature, the Pakistani military ought to invest in acquiring a satellite communications (SATCOM) network. SATCOM enables the user’s networked assets to communicate and exchange data at beyond-line-of-sight (BLOS) range. In other words, at long-range and/or in the midst of heavy natural obstructions, such as mountains. For example, special forces operatives deep within enemy territory could radio vital information to the satellite, which in turn would relay that information to a frigate, which could then use that information as targeting data for its cruise missiles. SATCOM also enables militaries to deploy high-altitude long-endurance (HALE) drones, which could be used to engage in surveillance work as well as air strikes in high-risk environments. These are but a few examples, but it is clear that SATCOM would strengthen Pakistan’s network-centric warfare capacities at the tactical as well as strategic level.

It is without a doubt that Pakistan has made genuinely strong strides in the development of its network-centric warfare capabilities, especially through the development of domestic data-link networks. The success of these programs has enabled the armed forces to acquire valuable capabilities, such as time-sensitive targeting (TST), among others. In addition, Pakistan’s capacity to source domestic data-link solutions has enabled it the freedom to scale its network-centric goals according to its own interests. While there is still considerable room for growth (e.g. SATCOM), the armed forces’ communications capabilities today are indispensable and praiseworthy assets.