76Views 1Comment

Pakistan’s Shift to COIN Part 3: Infantry and Light Armoured Vehicles

Continuing from Part 1 and Part 2 of ‘Pakistan’s Shift to COIN’

There are three groups to consider when looking at Pakistan’s infantry. First, the Frontier Corps, a paramilitary unit that technically falls under the purview of the Interior Ministry, but can come under the command of the Army. Second, the regulars, i.e. the standard infantry force belonging to the Pakistan Army. Third, the special operations forces (SOF) belonging to each of the service arms, such as the Special Service Group (SSG) with the Army, Special Service Wing (SSW) with the Air Force, and Special Service Group Navy (SSGN). Since 2005 each infantry group has seen itself shaped to undertake distinct operational roles in fulfilling the Pakistani military’s objectives in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). This article will offer some detail into the roles of the Army and the Frontier Corps in regards to Pakistan’s counterinsurgency (COIN) campaign, and how they changed over the past decade. An overview of SOF, including the hybrid SOF units (e.g. light commando battalions), will be done in a later article.

Background of the Frontier Corps and Relationship with the Army

The Frontier Corps was established in 1907 by George Curzon, the then British imperial viceroy presiding over India. In 1947 Pakistan inherited the Frontier Corps and has since used it as a paramilitary force (under the formal control of the Interior Ministry) in the North West Frontier Province (NWFP – later renamed Khyber Pakhtunkhwa). The Frontier Corps was divided into two overarching subdivisions, FC Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) and FC Baluchistan; combined, the Frontier Corps force stands at about 80,000 personnel.[1] The Frontier Corps is also supported by the Frontier Constabulary, a federal police force.

In certain situations, such as the military’s campaign in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), the Frontier Corps can come under the command of the Army.[2] Commissioned officers, especially at the command level, are also drawn from the Army. Unfortunately, assignment to the Frontier Corps was not (and to an extent still is not) seen as a progressive step for career Army officers. In fact, the underappraisal of the Frontier Corps in general, despite its immense physical input and importance in context of the regional realities, is a recurring theme.

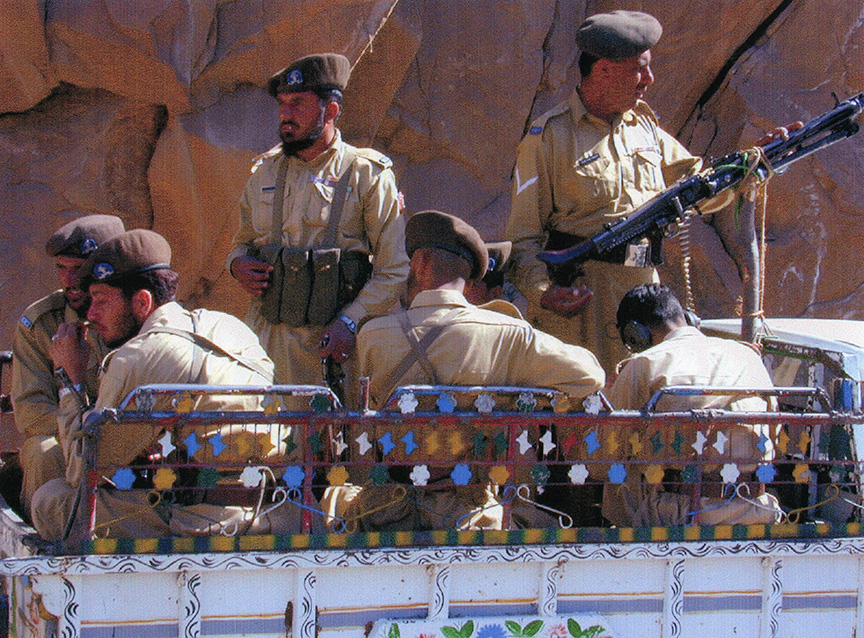

The Frontier Corps was involved in each of the Army’s major operations in FATA since 2002 (Al Mizan, Sher Dil, Rah-e-Rast, Rah-e-Nijat, etc). Although a general issue affecting the Army as well, deficiencies in basic infantry equipment were particularly acute with the Frontier Corps. Having lacked Kevlar bullet-resistant vests or modern ballistic helmets, the Frontier Corps was not equipped or trained for effective COIN. And this is at the most primary level (i.e. of the infantry), much less the lack of external material support the Frontier Corps have in the way of directly accessible armoured vehicles or aviation assets.

The Frontier Corps is a distinct entity, not only from an organizational or structural perspective, but the reality that its personnel are primarily drawn from the local Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa populace. Unlike the Army, which is a force composed of persons from across Pakistan and with a mandate to focus on the territorial boundaries of the country, the Frontier Corps is a regional entity with an internal mandate. Unfortunately, especially in the context of the FATA campaign, this reality has had its drawbacks. Prior to 2005, U.S officials noted that the Taliban were able to move “in broad daylight” between the Afghanistan-Pakistan border “under the noses… or even with direct assistance from the Pakistani Frontier Corps troops.”[3] This perception contributed to the Army’s distrustful disposition towards the Frontier Corps.[4]

Counterinsurgency Operations from 2002-2009

The problems presented by this aforementioned organizational gap were compounded by the fact that Pakistan’s infantry – paramilitary and regular alike – were not equipped and trained for COIN. In terms of equipment, for example, Frontier Corps soldiers wore sandals and World War I-era helmets, and were armed with bare-bone AK-47 assault rifles (i.e. without vertical forward grips or sights).[5] The condition of the Pakistan Army’s regulars was not much better, modern day combat helmets or body armour were a rare sight in the early FATA operations.

These deficiencies could be attributed to several causes. Firstly, the Pakistan Army was oriented towards fighting a conventional war with India, whose infantry capabilities and doctrines in the early-2000s were comparable. Infantry on both sides of the border were geared to move in large formations and were generally not expected to operate as small teams in built-up urban environments. Secondly, the Army leadership did not fully appreciate or understand the importance of well trained and equipped infantry in the context of COIN. In order to effectively deploy small teams to patrol towns and maintain presence, those teams need to be well-equipped, well-trained and well-supported (by intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance – ISR) assets. If not, as seen in Pakistan, there will not be very many patrols, and – also seen in Pakistan – the work to displace insurgents would occur through other methods. In Pakistan’s case, those methods were punitive in nature (involving air and artillery strikes), affecting the local population through civilian casualties and destruction of property and livelihoods.[6]

In 2008-2009 a shift began to occur in terms of the importance given to infantry, regular and paramilitary alike. There were multiple drivers behind this shift, not least the fact that the Democrats led by Barrack Obama were elected to take over the White House. Unlike the Republicans, who simply gave directives and the money to achieve them, the Democrats sought to closely direct Pakistan to achieve America’s foreign policy objectives in the region. However, 2008-2009 also marked a major surge in insurgent activity within Pakistan, not just at the hands of the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), but other militant arms as well, such as Tehreek-Nafaz-e-Shariat-e-Mohammadi (TNSM), led by Sufi Mohammad.[7] Whereas the TTP’s deep-rooted presence in Waziristan was understood, TNSM’s in-roads in Swat and Faqir Mohammad’s gains in Bajaur Agency, added an extra layer of concern in Islamabad (and Washington).[8] The fighting between these factions and the Pakistan Army’s 11th Corps came to a halt via a peace deal in 2009, which was harshly criticized by the West, but would later crumble by the summer of 2009.

Under the leadership of General Ashfaq Pervez Kayani, the Pakistan Army had begun to properly re-orient its ‘focus of the day’ from India to FATA, thereby making COIN a key pillar of its operational doctrine. In May 2009 the Army commenced Operation Rah-e-Rast to clear Swat district of the TNSM, and it was during this period that key changes in the infantry’s equipment, training and doctrine were beginning to take hold in the Army and Frontier Corps.

The most notable change during Rah-e-Rast was the widespread use of personnel body armour as well as the use of small teams to clear compounds and other built-up areas. Granted, the fact that the TNSM was an established force in Swat at the time of the operation made Rah-e-Rast a hybrid campaign: Heavy military force (e.g. air strikes) was used to displace the TNSM, but COIN was used to fully purge the area of any TNSM sub-haven in Swat. The scale of the operation resulted in as many as two million people from Swat being displaced.[9] However, the operation was also a turning point: It marked the start of the Army’s earnest transition into heavily focusing on COIN, and the results, such as the subsequent operations in South Waziristan (Operation Rah-e-Nijat) and even North Waziristan (Zarb-e-Azb), were apparent.

Counterinsurgency Operations 2010-Present

Matters were relatively cool in FATA from 2010 to 2014, with the Army primarily focusing on clearing South Waziristan. But Zarb-e-Azb, which was focused on North Waziristan, marked the most significant series of shifts in terms of Pakistan’s transition to COIN. Earlier operations in FATA would span at most a few months, and with the aim of ‘clearing’ an area of ‘miscreants’. Zarb-e-Azb, reaching about 18 months at the time of this article’s writing, is evidently different. It is a sustained and long-term effort aimed at not only clearing North Waziristan of every militant organization present (including the ones the Pakistani military was once sympathetic to, such as the Haqqani Network), but in ensuring that it does not become a future haven for insurgents, period.

In addition to appropriate personnel equipment, COIN doctrine and training was also fully incorporated during the time Zarb-e-Azb was in full swing. From a doctrinal standpoint, COIN had become a key aspect of the Pakistan Military Academy (PMA)’s curriculum; the man who propelled this to fruition, General Raheel Shareef, was selected as the Army’s Chief of Staff in 2013. In terms of implementation, the National Counter Terrorism Centre (NCTC) was established at Khariyan Cantt (Central Punjab) for commissioned and non-commissioned Army officers as well as personnel from Pakistan’s paramilitary and law enforcement agencies (LEA). The NCTC’s courses are multi-faceted: In addition to imparting specific skillsets (such as in fighting in built-up areas and operating in small teams), the NCTC also educates personnel on the nature of COIN (and perhaps more broadly, urban operations).[10] The NCTC trains over 3000 personnel a month.[11] There is no doubt that this program is going to have a significant impact in the coming years, especially on the paramilitary agencies (e.g. Frontier Corps and Rangers).

This will be discussed in more detail in a later article of this series, but the Army and Frontier Corps also have considerable support (compared to 2005) from the Pakistan Air Force (PAF). The infantry is no longer a standalone element, but it is supported by and networked to a wide range of aerial ISR assets. These assets include unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in the form of the Falco, C-130s equipped with FLIR Systems’ Star Safire III EO/IR sensor balls and F-16s equipped with UTC Aerospace DB-110 reconnaissance pods. Collectively, these systems offer Pakistani ground forces a comprehensive and up-to-date picture of the ground. In addition, the PAF also engaged in precision-guided airstrikes (it has laser and satellite-aided munitions at its disposal) using its F-16s, Mirages and JF-17s. Armed drones in the form of the NESCOM Burraq are also available and have been used.

In terms of equipment, Zarb-e-Azb also saw the introduction of new armoured vehicles for personnel transport, most notably the Navistar MaxxPro mine resistant ambush protected (MRAP) vehicle. These vehicles, with their V-shaped hulls, are designed to deflect the blast of a mine away from the vehicle, thus protecting the occupants. The Pakistan Army ordered 160 MaxxPro MRAPs from the U.S for $198 million in September 2014.[12] It is unclear if Pakistan is looking to acquire additional MRAPs, especially considering that – prior to the above purchase – it was looking to acquire “a lot” of MRAPs through the excess defense articles (EDA) program.[13] Pakistan has yet to officially request for MRAPs under the EDA (in addition to the order made in September 2014). That said, it is evident that the MRAPs will play a major role in the Army (and potentially Frontier Corps’) patrol and presence operations.

In addition to the MaxxPro MRAPs, it seems the General Dynamics Land Systems (GDLS) Dragoon four-wheeled armoured fighting vehicle (AFV) will also be inducted. The Dragoon was originally developed for use as a base security APC in the 1980s, but since its introduction it has been adopted by LEAs and paramilitary entities in numerous countries. Heavy Industries Taxila (HIT) is producing the Dragoon under license, and is marketing it with “bottom anti-mine, anti-armour” capabilities.[14] Though not an MRAP, compared to the Toyota pick-up trucks grafted with machine guns, the Dragoon should fare as a sizable upgrade for the Army and Frontier Corps in FATA, as well as the other paramilitary arms and LEAs in need of affordable and versatile armoured vehicles. There are several neat things about the Dragoon: First, it shares some commonality with the M113, which is in wide use with the Pakistan Army.[15] Second, the Dragoon can be built in the form of different variants, such as the ‘mobile electronic warfare system’ (MEWS). In this format the Dragoon could serve as a land-based intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) system where its electro-optical systems can be paired to onboard data-link, giving commanders in the rear a clear view of the ground situation.

Although not exclusively related to the COIN effort, the Pakistan Army was also seeking a larger wheeled AFV design. It evaluated the Serbian Lazar II, but opted for the Chinese VN-1 8×8 AFV and was in talks to have it produced under license.[16] In all likelihood, the COIN effort could do well with additional MRAPs and Dragoons, the VN-1 acquisition is more in line with the Army’s overall needs, namely the idea of supplementing its large fleet of tracked APCs with wheeled AFVs. Even though tracked systems such as the M113-derived Talha and Saad APCs are good for desert environments, the reality of increased road development in the region as well as the prospect of state-to-state war in mountainous areas such as Kashmir make wheeled AFVs a necessity. The VN-1 could be adapted for a wide-range of roles as well, from very short-range air defence (VSHORAD), self-propelled artillery, land-based ISR, medical transport and evacuation, to name a few.

Considerations for the Future

From a structural standpoint, the paramilitary units should in general be inherently well-equipped, well-trained and well-funded entities. Strong and, more importantly, professional paramilitary entities would enable the Army to fully return to defending Pakistan’s borders without compromising on the country’s internal integrity. It is possible that this will take place in the coming years as more Frontier Corps personnel are rotated into the NCTC, but it is imperative that other key aspects of the COIN effort are transferred to the Frontier Corps as well.

For example, MRAPs and light armoured vehicles (LAV) such as the Dragoon should become commonplace with the Frontier Corps as these are vital tools for essential COIN duties. Moreover, certain close air support (CAS) and ISR elements should also be made directly available to the Frontier Corps. These could include lightweight aircraft equipped with FLIR and other electro-optical sensors and/or perhaps even a dedicated aviation unit with proper utility helicopters. Perhaps new SOF or quasi-SOF arms could also be raised within the Frontier Corps (and other paramilitary arms) to supplement (if not supplant) the role of the SSG (except for the most dangerous or critical operations)?

In the end, the efficacy of paramilitary agencies in being the first (and ideally only necessary) line of defence against any kind of insurgency is going to depend on the professionalism and adaptability of those agencies. The idea of a ‘second tier’ military must be abandoned, and in its place, the idea of a fully professional and upward oriented (i.e. it attracts eager and competent personnel) service arm uniquely trained and equipped for internal security must rise.

[1] Seth G. Jones & C. Christine Fair. “Counterinsurgency in Pakistan.” RAND National Security Research Division. 2010: p38

[2] Ibid. p35-36

[3] Ibid. p39.

[4] David J. Kilcullen. “Terrain Tribes and Terrorists: Pakistan, 2006-2008.” Brookings Counterinsurgency and Pakistan Paper Seires. No. 3, 10 September 2009.

[5] Azeem Ibrahim. “U.S. Aid to Pakistan – U.S Taxpayers Have Funded Pakistani Corruption.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. July 2009. p6

[6] Kilcullen.

[7] Jones and Fair. 2010: p25

[8] Ibid. p25-27

[9] “Pakistan military confronts Taliban in key Swat city.” CNN. 23 May 2009: http://www.cnn.com/2009 /WORLD/meast/05/23/pakistan.fighting/index.html?iref=24hours

[10] Lt. Col. Amjad Raza Khan. “Conduct of National Integrated Counter Terrorism Course.” Hilal Magazine. June 2015: http://hilal.gov.pk/index.php/layouts/item/1429-conduct-of-national-integrated-counter-terrorism-course

[11] S.C. Kohli. “NCTC: Pakistan’s newly established anti-terrorism centre.” Merinews. 22 October 2015: http://www.merinews.com/article/nctc-pakistans-newly-established-anti-terrorism-centre/15910614.shtml

[12] “Pakistan – Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) Vehicles.” – Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA). 19 September 2014: http://www.dsca.mil/major-arms-sales/pakistan-mine-resistant-ambush-protected-mrap-vehicles

[13] Jeff Schogol. “Pakistan, Afghanistan, India Want Leftover US MRAPs.” DefenseNews. 1 April 2014: http://archive .defensenews.com/article/20140401/DEFREG04/304010030/Pakistan-Afghanistan-India-Want-Leftover-US-MRAPs

[14] Dragoon Armoured Security Vehicle. Heavy Industries Taxila: http://www.hit.gov.pk/dragoon.html

[15] Ibid.

[16] Usman Ansari. “Experts Say Pakistan-US MRAP Deal Likely To Win Approval.” Defense News. 23 September 2014: http://archive.defensenews.com/article/20140923/DEFREG03/309230040/Experts-Say-Pakistan-US-MRAP-Deal-Likely-Win-Approval